The discovery of a ship sunk during the First World War shows the power of multibeam sonar in maritime archaeology. The wrecks of the world’s seas have a lot to tell; here are a few stories.

In April 1912, the British merchant ship Mesaba was steaming across the North Atlantic when the crew spotted several icebergs at sea. Mesaba’s electric starter sent a warning to other ships, and the threatened Titanic, on its maiden voyage, was also alerted.

But it was so unfortunate that the message never made it to the bridge of the Titanic. Later that evening, the Titanic crashed into an iceberg. More than 1 500 people drowned in the disaster.

Six years later, Mesaba’s journey also ended at the bottom of the sea. A torpedo from a German submarine sank Mesaba and her crew of 20 at the very end of the First World War in 1918, as she was escorting a convoy from Liverpool to the United States.

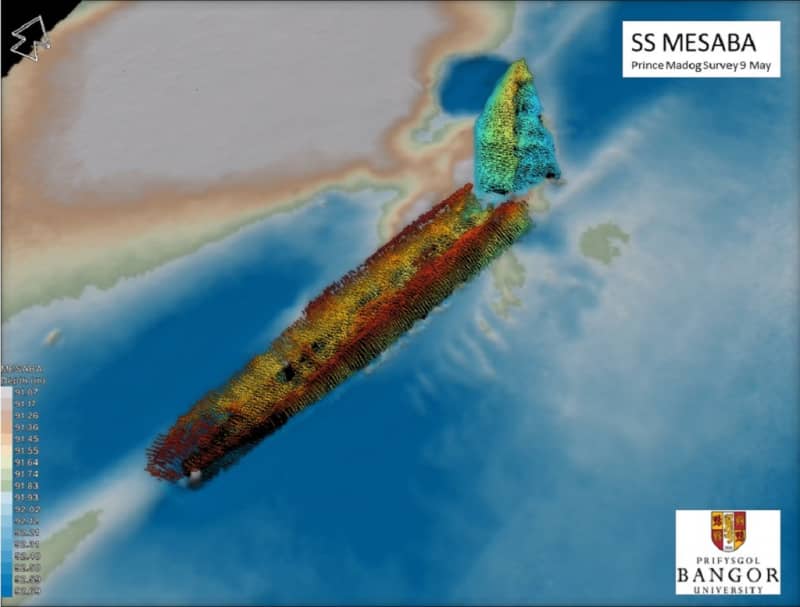

Mesaba was off the coast of Ireland when it was hit. Although the fate of the Mesaba was seen by other ships in the convoy, the wreck’s place among many others resting in the same area has been unclear. The riddle was solved in a recent study using a new method.

A total of 273 ships were observed in the study area of \u200b\u200bmore than 19,000 square kilometers. Marine archaeologists from the British University of Bangor stated that the Mesaba has been mistaken for a wrong wreck.

In addition to Mesab, several other wrecks were now correctly located. The group includes both fishing and ocean vessels as well as submarines.

Mesaba was found without diving, with the help of a multi-beam sonar that bombards the seabed with sound waves. What it said was compared to several databases where data on wrecks in the Irish Sea have been gathered.

The use of the method in marine archeology is revolutionary, says Roberts. He compares the accuracy to how much archaeologists working in the country get out of aerial photos.

The price is also much lower than in traditional tracking. In Bangor University’s research, the price of identifying each wreck came to about one thousand euros.

Bangor University could only afford to locate a few wrecks a year when they had to be dived to look at them. The research vessel Prince Madog is capable of recovering up to 25 wrecks per day, says Roberts.

– Many are in depths where light does not reach. Visibility there is very poor. A diver swimming end to end of the wreck will also never get the same pictures of it as we do. Because of the sediment, you just can’t see everything.

Three stories of three million

Man has been sailing on water since the Stone Age, and accidents have always happened. No one can swear to know how many wrecks lie in the world’s oceans. The UN scientific and cultural organization Unesco estimates the number at more than three million.

Sunken ships are a huge historical archive of a bygone world. Despite the development of research methods, only a very small part of the wrecks can be found, let alone be studied, but the following three discoveries announced in recent months, for example, are opening windows to a time that no longer exists.

Even the famous wreck’s wine bottles speak politics

Contemporaries told after James’s death, when they dared, that James had determined the ship’s route in a sense of his power, even though the captain disagreed. Up to 250 people died in Haveri. James was saved and became the last Catholic king of England, Scotland and Ireland.

– By openly drinking French wine, James perhaps wanted to defy Parliament and show himself to be above his subjects.

The story of the German submarine continues to surprise

In its long article, it tells about the search, which ended last month: U-111, part of the submarine fleet of the German Empire, was found off the coast of the state of Virginia, where it had been rusting in a salt bath for a hundred years.

Built at the end of the First World War, U-111 managed to sink three merchant ships before Germany’s defeat took her to Britain among the German ships to be scrapped. The story could have ended there, but there were many surprising twists.

They didn’t want to destroy all the ships at once. The winning nations decided to smash a few first to find out their technical secrets. The US wanted a few submarines to tour their east coast as well, to raise money for war recovery.

U-111 was not among the ships to be spared, but got to it when it appeared that one of the initially chosen ones had been sabotaged by agents of both Germany and surrounding powers to prevent the other side from profiting from it.

More than half of the crew had never even been on a submarine, and the rest of the crew were completely unfamiliar with the German’s modern navigational device, the hydrocompass.

After four days at sea, a trap set by German saboteurs nearly sank the ship, soon after that food ran low, and fuel ran out far from the destination. The crew already had time to think about improvising the mast and sail.

However, U-111 made it to New York, did its tour and had to reveal its secret. Then it was supposed to be air-bombed at sea in a spectacular way, but again it turned out differently than planned: U-111 escaped from its tugs and sank on its own near the shore.

There was not even enough shallow water to completely cover the ship, so it was raised and towed out to sea. There, its hatches were opened, and U-111’s multi-generational story ended at a depth of 120 meters, 65 kilometers off the coast of Virginia.

Levant’s international merchant ship defies the history books

Between 1,300 and 1,400 years ago, a ship loaded with trade goods from different parts of the Mediterranean ran into trouble off the coast of present-day Israel and disappeared in the shallow waters of Ma’agan Mikhael.

At that time, big political and religious changes were going on in the Levant at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. The Christian empire of Byzantium was dying and Islam gained more and more ground.

– History books claim that international trade was almost completely cut off. It has been assumed that there were only small ships in motion near the coast, between the ports of their own countries. That doesn’t seem to be the case, says Cvikel.

The wreck is large, 20 meters long and five meters wide. Cvikel estimates that the ship was originally 25 meters long.

The sandy bottom of the sinking area has protected the wreck. It was tracked down when the divers noticed a piece of wood that had split off the bottom of the storm-tossed sand. The study was completed last month.

The cargo shows that the ship had called at ports in Cyprus and Egypt, possibly Turkey and even as far as the coast of North Africa. Some of the cargo had symbols of the Byzantine Church, others had Arabic writing.

When the researchers had vacuumed a one-and-a-half-meter layer of sand from the top of the wreck, 200 amphorae were revealed underneath, containing, among other things, the typical fermented fish sauce of the time, various olives, dates and figs.

In addition to complete amphorae, pitchers, bowls and their fragments were found in the wreck as well as glassware, combs and other wooden objects, coins, bricks and stones used as ballast. There were also signs of lightning drivers: the bones of six rats.

Researchers hope to find a place for the wreck where it can be put on display in its entirety. Otherwise, it will be hidden back on the seabed among the countless other wrecks in the Mediterranean, Cvikel tells the Reuters news agency.