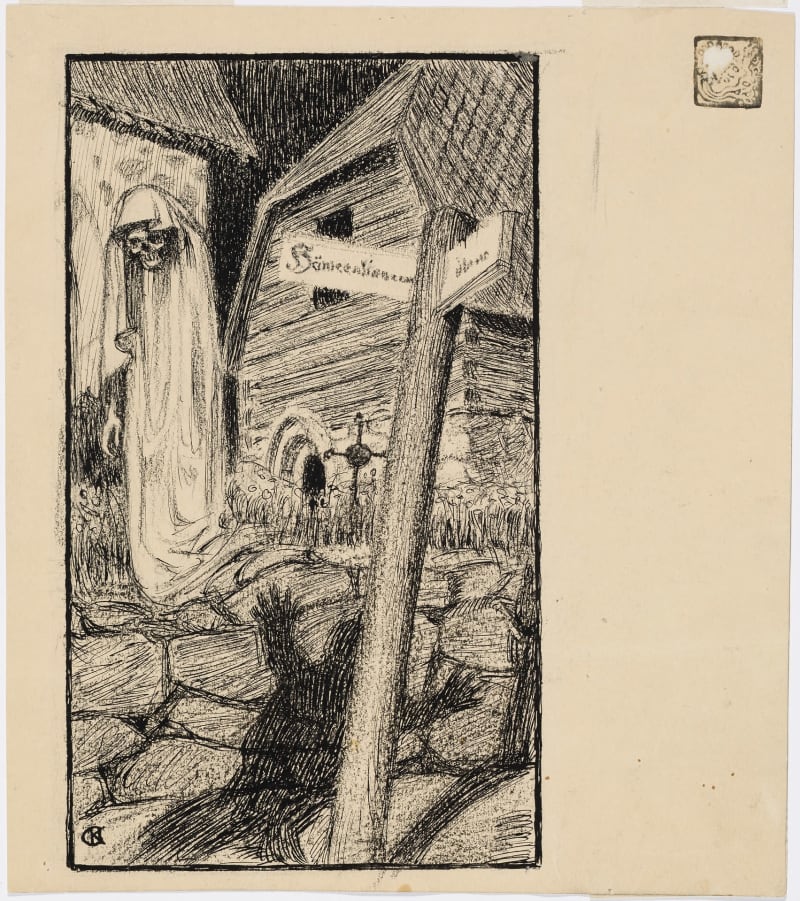

Pasi Klemettinen’s book \”The Night Side of Folk Beliefs\” presents creatures left in darkness, which have played a significant role in Finnish mythology and which have also influenced the everyday life of Finns.

While doing his dissertation, Klemettinen became interested in the villains and freaks of folklore and mythologies already twenty years ago, when he noticed that there were a lot of them in old publications. is the first broader survey of its kind on the topic.

– In the past, folk traditions have perhaps mainly wanted to highlight positive and positive aspects of culture, such as, for example, god figures who have helped in the cultivation of grain, Klemettinen reflects.

God figures and heroes who preach goodness – after all, a hero wouldn’t be a hero without a victorious battle – have, however, demanded counter-forces, and at this point the bad guys have entered the picture. Throughout time, there have been parties that have tried to prevent or make it difficult for human activity, and the majesty of Finnish nature, with its dense forests and dark seasons, has been the icing on the cake.

– In certain places, even today, people can be scared and horrified after dark. You can only imagine the time before electricity and electric lights: when you’ve had to move in the dark, all kinds of things have surely come to mind.

The Finns’ relationship with nature has mostly been romanticized and described as harmonious, but based on the book, things have not been quite so open. The forest has been full of scary and dark creatures, such as the restless spirits of slain children, i.e. woodpeckers or leafhoppers, which cry, scream and screech eerily at night.

– The range of such creatures is huge. You could say that evil beings can be found in a similar way and as much as there are good possessors attached to a certain place, sums up Pasi Klemettinen.

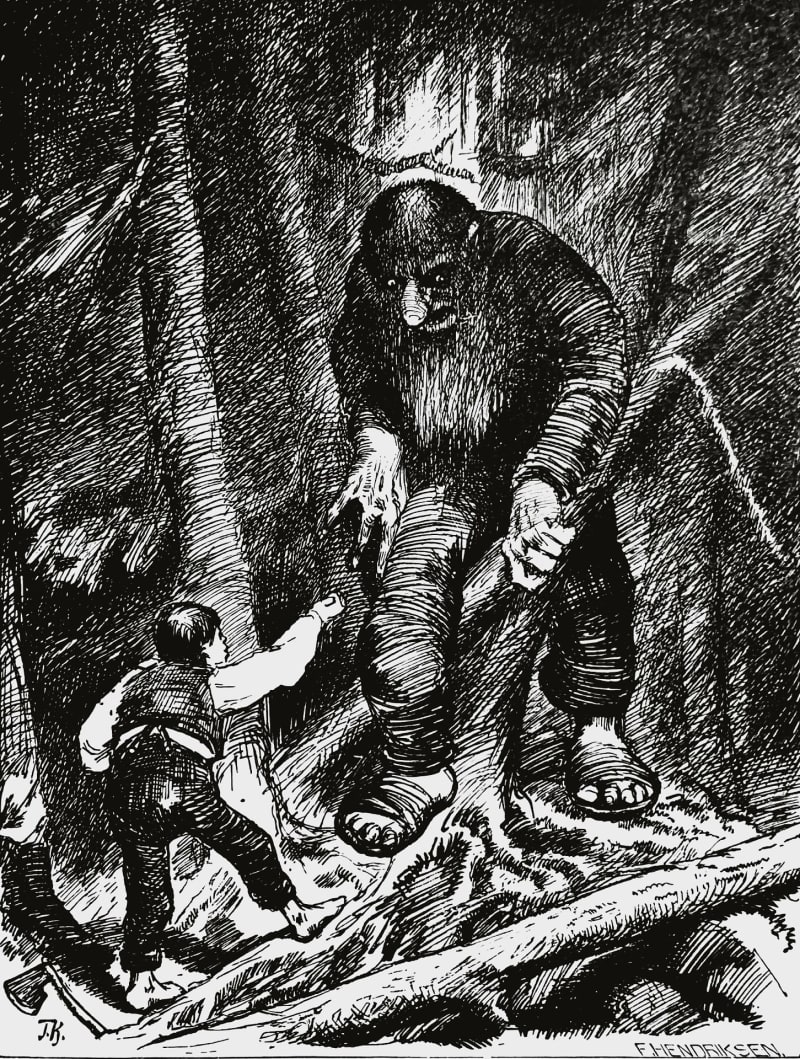

Among other things, the forest has been inhabited by a dangerous, ugly-voiced, laughing female forester, ajattara, who misleads and misleads travelers. A large, black-eyed forest devil, or barren, once again teased people for fun.

Even the waterways of the land of thousands of lakes hide horrors in their depths. Näkki could be disguised as a log or log, carrying unsuspecting swimmers, especially children, far upstream to drown. The sight was still feared in Finland at the beginning of the 20th century: if suspicious marks were found on the body of a drowned person, the cause of the sight was the compression of the claws.

Demons rode domestic animals at night

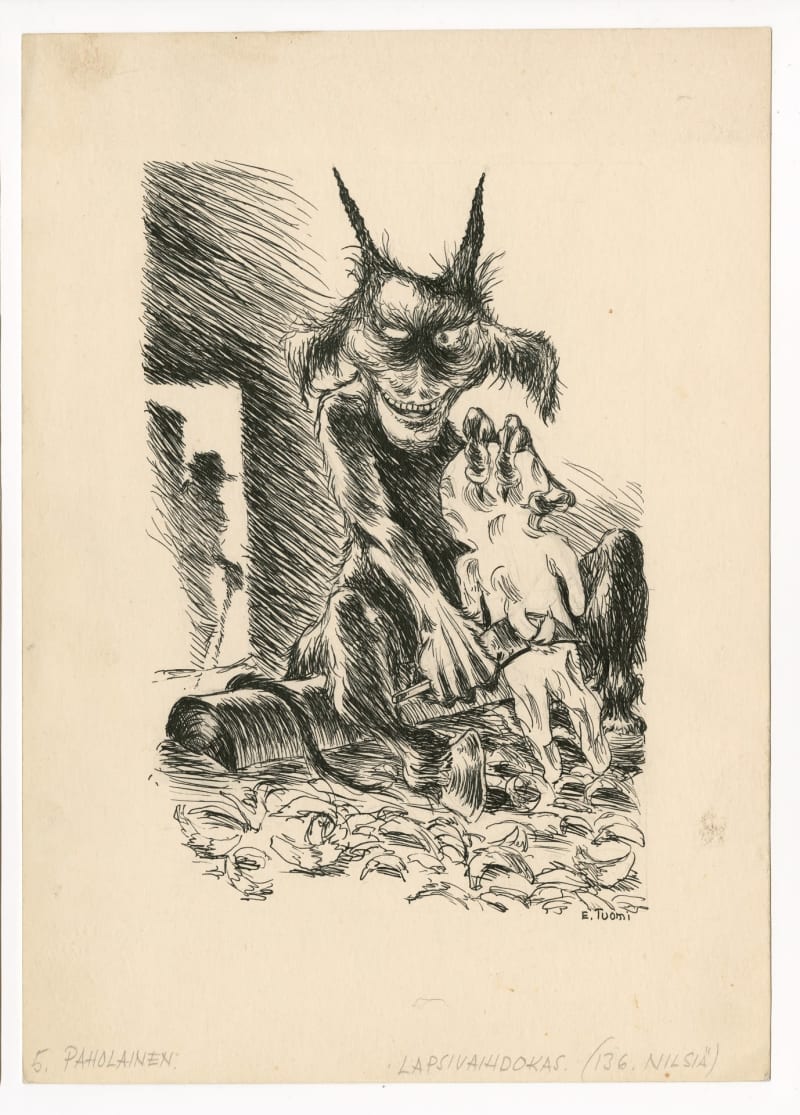

Finland was largely an agrarian society until the 1950s, so it’s no wonder that evil spirits and bully creatures have roamed the barns and stalls and haunted cattle and domestic animals. It was a common belief that if a horse or cow panted in the morning exhausted, frothy and restless, a demon called ajajainen or ajaikas had ridden during the night.

You could try to drive away the evil demon by putting, for example, a thistle blanket on the animal’s back at night, on which it would be difficult for the troublemaker to sit. A mirror could also be attached to a cow or a horse, in which case the ugly-faced demon would be scared of its own image and would run away. Riders and riders were believed to be the result of black magic.

– Since in those days there was no medical explanation, let alone doctors, who would have explained what caused the diseases of animals or people, they relied on soothsayers, witches and healers. They have had mythical explanations for how evil has come from the other side and how it can be banished by casting spells or by applying spells, says Pasi Klemettinen.

When people’s diseases and pains were to be exorcised, the Mistress of the Pain Mountain or Kivutar, who had already appeared in Kalevala mythology, was called to help. He has had a motley coffin in his arms, in which the pains have been pushed.

On the other hand, Kivutar has also appeared as a devilish damsel, whose pains cooked in her bubbling cauldron have been able to be cast out by the witches into people’s troubles. A similar role has been played by Lovettar, the carrier of all diseases, who gave birth to nine sons, i.e. the disease demon. These disease demons are described by, among other things, horkka, bone light and abscess.

Lovetar has also given birth to one daughter: Söjätär has created various plagues to torment people, and is described as a destructive creature that has \”eaten a hundred men and destroyed a thousand males\”.

– Of course, someone may wonder why there are so many similar female characters in such a mythical world. I would consider that it is not a male discourse or thought model that demonizes women, but in all its simplicity and concreteness this is related to a woman’s physiology and ability to give birth.

Piru is a perennial favorite of folklore

The most popular villain in domestic folklore is definitely the devil. This is also evidenced by the fact that the beloved child has numerous nicknames such as lempo, sarpinää, irvihammas, hooves, pikanokka, peijakas and rietas. As a feared figure, the devil has come up with catchphrases, which, of course, are also often accompanied by mockery and humorous features.

– Many creatures have been forgotten over the years and completely disappeared from folklore, but the devil is still an enduring favorite and a prevailing belief creature. It has lived up to these days and we also have Satan worshipers and religious sects for whom the devil is very real, says Pasi Klemettinen.

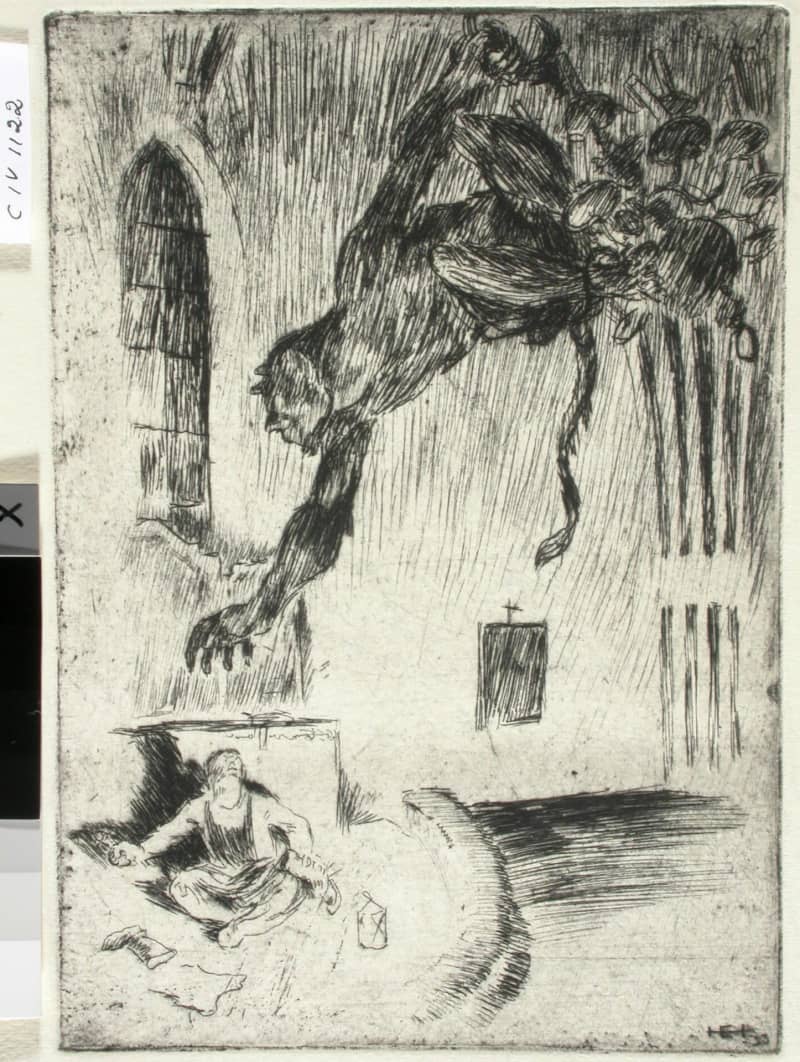

In Finnish folklore, the malevolence of the devil is associated, for example, with sauna culture. Taking a sauna after midnight used to be taboo, and the devil could punish such people in a way straight out of a horror movie:

– , in a story recorded in Vihti in 1936, it is told.

The vitality of the devil in folklore was supported by a surprising entity: the church strictly forbade believing in and worshiping such creatures. At the same time, however, the church admitted that they existed.

– The information war turned against itself, as it were. It’s Finnish nature that if something, for example alcohol, is forbidden, then only then do we get excited about it, sums up Pasi Klemettinen.

Giant snakes belch poisonous gases

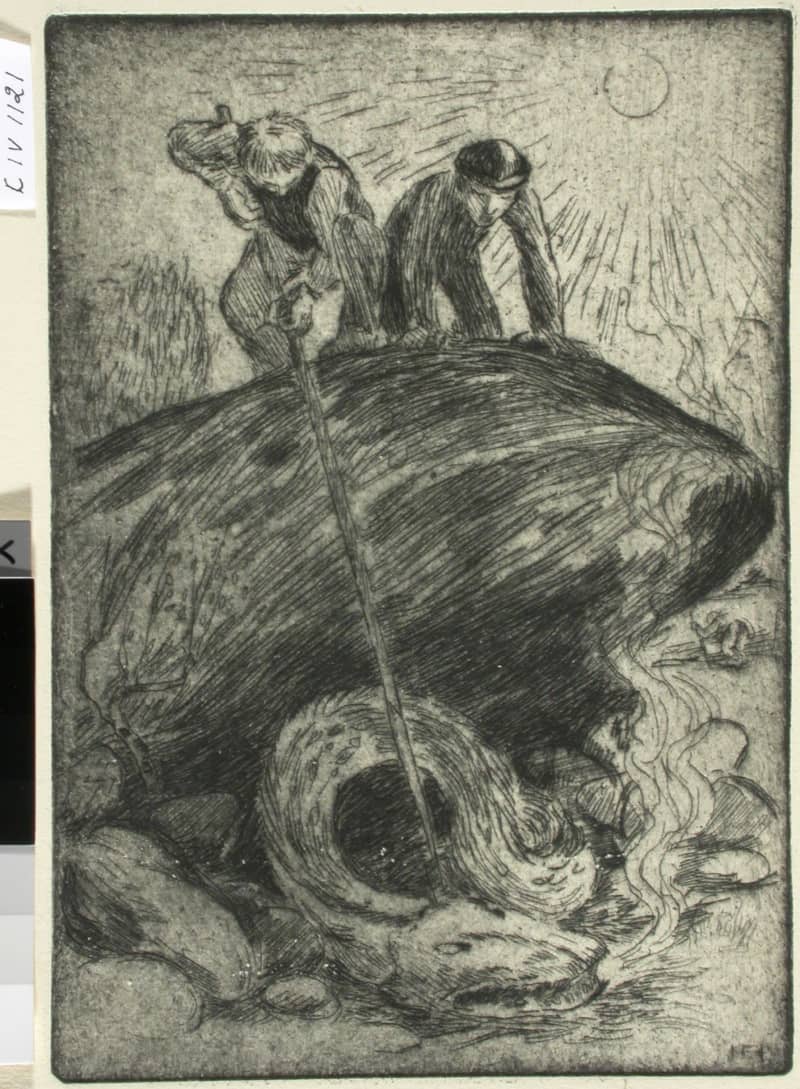

In the book Pirun ohella you come across many versions of snakes, one of which is Tuonen’s caterpillar, or more commonly called viper.

– In the case of the viper, it is interesting how a relatively harmless small animal has grown into a huge mythical creature, Pasi Klemettinen states.

Thus, in folklore, there are numerous references to creepy giant snakes chasing people and spewing poisonous gases from their gills. The snakes are not content with just crawling, but they have gone into a ball and circled behind human hair like a cart wheel.

– , says a record from Jalasjärvi from 1961.

Observations of flying giant snakes have also been made in Finland. In 1895, local sailors said that they saw a flying snake above Laatoka.

The dragon, on the other hand, is not only a creature belonging to the Asian cultural circle, but they have also been seen in Finland. The native dragons, or Thracians, have had \”a cat’s head and yellow ears\” and their venomous rampages have dried up large parts of the surrounding forests.

True or false?

-the world view offered by the book naturally raises questions: is it really believed, for example, in the vetheis, which has tried to capsize rowing boats, or the kelp, which are headless dead creatures?

According to Pasi Klemettinen, some of these creatures and stories were once considered real.

– Maybe you don’t believe in mountain goblins who throw stones at people and destroy churches, or dragons. Of course, you can ask in what sense these things have been told, especially if it has been emphasized that a villager has actually seen and experienced this thing himself.

Some of the stories have had not only a teaching and warning purpose, but also an undeniable entertainment value.

– They are like good horror stories. A monster pops its head out of the water and people run away, but this doesn’t always lead to a more detailed explanation of the creepy experience — at least not in the world of stories.