The Atacama desert in Chile has the world’s largest lithium reserves. The green transition increases the demand for battery metal, but the indigenous people of the area fear that their habitat will dry out even more.

Lithium, known as white gold, is needed for electric car batteries, for example. In turn, they are needed for emission reductions, which aim to curb global warming.

But at what cost?

The surroundings of Suolapannu, next to the Andes Mountains, is also the home of the Lickanantay indigenous people.

The Atacama desert is a central place in terms of combating climate change. Chile produces two lithium companies, the Chilean Sociedad Quimica

However, the Lickanantay natives fear that mining will further dry up their ancient homeland.

– It is a very sensitive and vulnerable ecosystem.

Lithium is extracted in sunlight

Salt pans are created in deserts under certain conditions over thousands of years, for example as a result of lake evaporation. The salt contained in the evaporated water remains to coat the ground.

– The concentration of lithium here is many times higher than other salt pans in Argentina, Bolivia or Chile, says Tore.

Lithium is extracted from a solution pumped underground, which has ten times the amount of salt compared to seawater.

Salt water is pumped into huge pools. Simply put, the lithium content of the solution is increased in tanks by evaporating the water and separating magnesium and other excess metals from it.

The evaporation process takes a good year.

– The process is completely natural. There are perfect radiation, wind and drought conditions for evaporation, and no additional chemicals are needed to increase the lithium concentration, says Tore.

The lithium will eventually be taken 350 kilometers away from the salt pan area to the mining companies’ chemical plants located in Antofagasta.

Mining companies pump a total of about 2,000 liters of salt water per second.

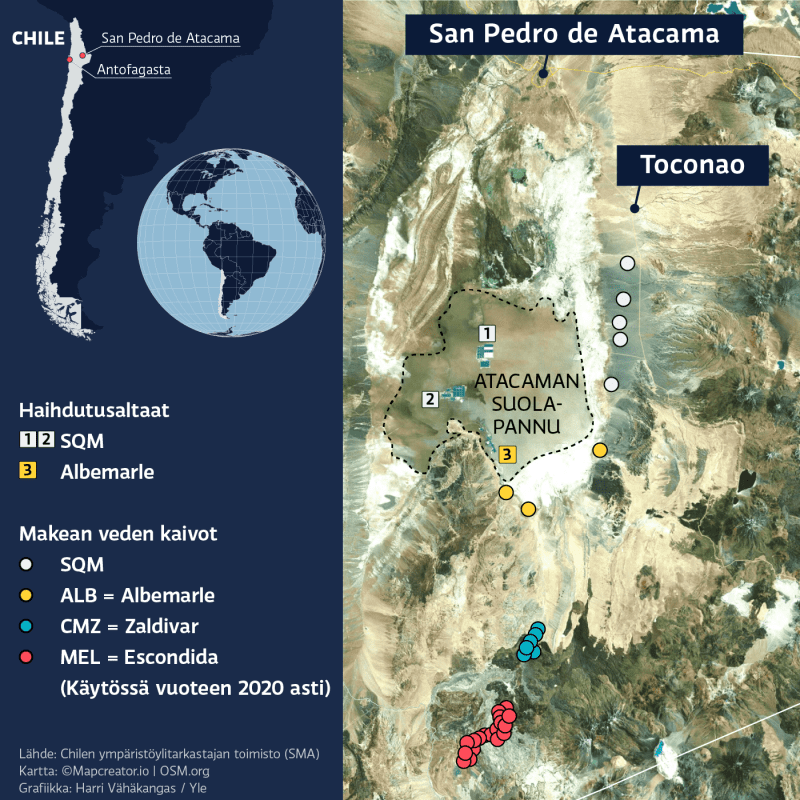

Moving the brine solution from one pool to another in the evaporation process also requires fresh water. Mining companies pump it from groundwater reserves in front of the villages on the edge of the salt pan at 140 liters per second.

Mining companies before the court

The Atacama desert is a naturally dry environment. However, plants, animals and human communities have adapted to its demanding conditions.

For example, llamas are grazed in the desert and small-scale farming is practiced in the desert oases. The flamingos that feed in the lagoons on the edges of the salt pan play a special role in the sacred rituals of the Lickanantay people.

Now local residents say that their living environment has changed. Fewer and fewer flamingos seem to be feeding in the lagoons, and the wetlands on the edges of the salt pan seem to be drying up.

– We don’t know why. But I think it’s clear that the watershed is an entity whose balance is being disrupted by lithium production, says Cabezas, who also serves as president of the local farmers’ association.

The Council of the Atacama Peoples (CPA), which represents the lickanantay community, also reports on environmental changes.

Salt water is no more suitable for human or animal use than for irrigation. This is one factor that SQM says lithium mines do not affect the region’s ecosystem. According to the company, the pumping of fresh water has also not caused any changes to the environment.

– According to several studies and our own understanding, the salt water concentration and the freshwater groundwater areas are separate systems from each other, says SQM’s Corrado Tore.

Science is not unanimous about the environmental effects of lithium mines. According to a recent study, climate change and natural variability also have their own effect on environmental changes. However, the latter study states that water permits have been distributed to mines beyond the carrying capacity of the salt pan.

– It is a very complex system, says Ibarra.

According to Ibarra, it is clear that the different parts of the salt pan have an effect on each other. However, connecting individual changes to a single mine is difficult.

Fresh water is also pumped from the Atacama salt pan for the mining of another important battery metal, copper.

Antofagasta company’s copper mine Zaldivar uses 500 liters of fresh water per second. The real geyser was the world’s largest copper mine, BHP’s Escondida, pumping fresh water at 1,400 liters per second until 2020.

In recent years, the Chilean authorities have accused all four companies of excessive water use. In the spring, the Chilean state sued the lithium mine Albemarle and the copper mines Escondida and Zaldivari for \”serious, permanent and irreversible\” harm to the environment and indigenous people.

The companies have denied having broken contracts or caused environmental damage.

SQM, on the other hand, has been at the mercy of the Chilean state since the authorities discovered in 2016 that the company had been pumping salt water above the permitted limit for years.

At the end of August, after a long process, the state approved SQM’s sustainability plan. Among other things, the company commits to halving both salt water and fresh water pumping by the end of the decade – while increasing its production at the Antofagasta chemical plant.

– In fact, we are already pumping only half of the amount of fresh water that the environmental authorities allow, Corrado Tore, head of hydroecology at SQM, tells Yle.

Both SQM and Albemarle also monitor the water situation in the area and submit their data to the authorities.

The native demands participation in decision-making

According to the CPA representing the Lickanantay people, the central problem is that the Chilean state has not implemented the international labor organization ILO agreement it ratified, which obliges indigenous peoples to be consulted when mining permits are issued.

According to the CPA, the lickanantay community was bypassed, for example, when agreeing how SQM could offset its environmental impact. The CPA took the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The matter has not been resolved yet.

The Chilean state does not recognize the country’s indigenous peoples in its constitution. The new constitution, which was defeated by a referendum in September, would have changed the matter. The draft constitution sought to emphasize the say of indigenous peoples in their territories and to limit the water permits distributed to mining companies.

\”You don’t see electric cars here\”

The inhabitants of San Pedro de Atacama, located in the northern part of Chile, have a long history in the shadow of the mines. For example, copper has been mined in one form or another for hundreds of years.

Last year, the mining industry accounted for approximately 15 percent of Chile’s gross domestic product. Industry is concentrated in the northern part of the country.

– Community life began to crumble when men moved to paid jobs in the mines and women were left with child care, farming and animals. The change has brought, among other things, alcoholism, Ramos tells Yle.

Of course, the mines have brought jobs, money and technology, says Ramos.

– I tend to say that we are the richest indigenous people in the world.

However, the income is not evenly distributed.

– There are people here without running water. People lack the training needed to defend the community and the Chilean state is responsible for this.

– You don’t see electric cars here.

According to several people living around the Atacama salt pan interviewed by Yle, the mines have caused conflicts within the communities.

For example, the mining agreement between the Chilean government and SQM obliges the company to allocate part of its profits to development work in the area of \u200b\u200bindigenous peoples. For example, SQM has built a water supply system in a village called Camar on the southeastern edge of the salt pan and has been involved in establishing a winery in Toconao. Since they are projects, their long-term or comprehensiveness is questionable.

Activist Rudecindo Cristian Espíndola, who lives in the village of Toconao, says that the agreements are good neighbor politics.

– This is absolutely minimum compensation. Where is the state of Chile? The state has abandoned the indigenous peoples. The development we are talking about has not arrived here.

Demand is growing

The demand for lithium is expected to grow, for example for the needs of electric cars and wind turbines. For example, the EU’s need for lithium will increase 60 times by 2050.

Chile wants to expand the lithium trench further south to the Maricunga salt pan. In particular, the local colla community has taken up resistance, fearing that the indigenous people will have to pay too high a price for the green transition.

These questions are not just about Chile and its salt pans. Chile is part of the so-called lithium triangle together with Bolivia and Argentina. The region has more than half of the world’s lithium.

While Chile has the world’s largest concentration of lithium suitable for mining, Argentina and Bolivia are estimated to have the world’s largest lithium deposits. They are still largely unused.

– We do understand the need for lithium. We are not against its production, as long as it is carried out responsibly and in compliance with international agreements, says CPA’s Mondaca.

– But when we talk about clean energy, we have to ask, where is it clean? Here where it is produced or in Europe?