Humpback whales learn the complex songs of other populations quickly and accurately when they hear them along their migrations. An equal cultural exchange is known only from humans.

Humpback whales seem to be as interested in new hit songs as people are. Whales are happy to pick up on a new song developed by another population, and it quickly spreads thousands of kilometers away, says an international study published in The Royal Society Open Science.

The researchers noted that the song, which was already known to have spread from eastern Australian waters to French Polynesia, had continued its journey to the coast of Ecuador. In a few years, the song had accumulated more than 14,000 kilometers of sea travel across the entire South Pacific Ocean.

The song of his journey had folded unchanged, although it is not a simple chant. The structure is more like human language. Short sounds, or units, are combined into sentences, and the whale builds themes from them. Each song consists of several themes.

Song transfer between humpback whale populations was first observed in the 1990s off the west coast of Australia. Its whales had caught on to the themes born on the east coast, and a couple of years later nothing else was sung in the western waters.

The songs have been compared to jazz jamming, where a repeating theme can stretch into an hour-long session. In the scope of song culture, only humans can compete with humpback whales, the researchers say.

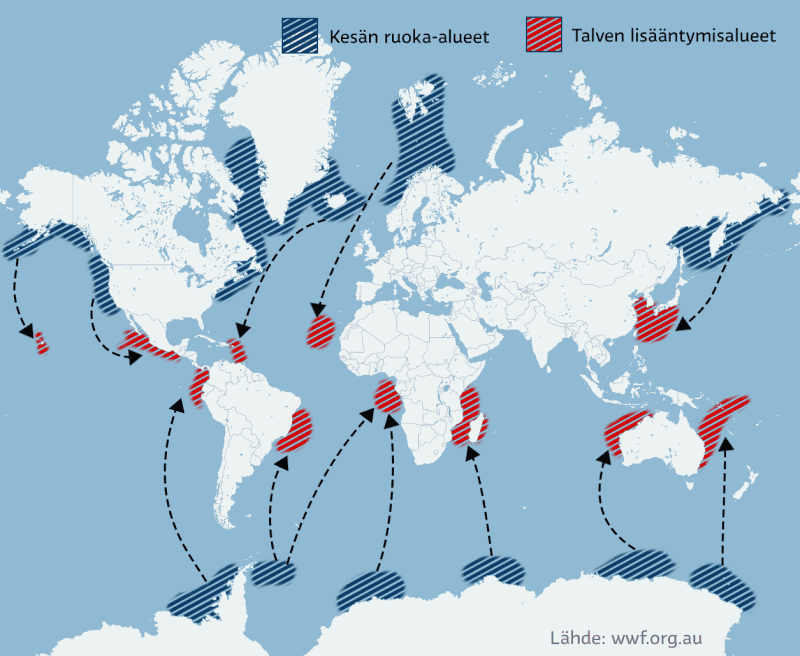

Every year, humpback whales migrate thousands of kilometers from the feeding waters of the polar regions to the breeding waters of the tropics. The whale lives in the breeding area for months without eating, after properly refueling with krill and fish.

How can whales learn each other’s songs in oceans where populations do not reproduce in the same areas and the distances are huge?

According to the researchers, encounters most obviously happen, even if a person has not been able to observe them. As big as humpback whales are, there is very little information about their migration routes.

At the crossings of the routes, the whales are offered opportunities to pick up another population’s new tune as their own – and it can be successful, even if you don’t meet the snout: the whale’s song has been found to be carried in the sea at least tens of kilometers away.

A recent study highlights one place where songs may be transferred: a staging post was recently discovered off the coast of the Kermadec Islands that appears to be used by several different populations.

It’s a thousand kilometers to New Zealand, and Tonga is just as far in the other direction. You can listen to the humpback whale’s song recorded from the sea by following this link.

It has been known for a long time that whales don’t just sing after arriving at the breeding ground, but also train along the way.

Garland was also involved in another international whale study that appeared in the Scientific Reports magazine in the spring. It explained how precise learning songs is.

Six songs were studied that were transferred between 2009 and 2015 from eastern Australian whales to New Caledonian populations. The results showed that even the most difficult patterns were completely unchanged in New Caledonia. Learning had not claimed to facilitate them.

The findings of the study support the hypothesis of encounters along migration routes or in areas where several herds come to feed, the researchers concluded.

The increasing understanding of humpback whales’ behavior, movement and mutual communication will provide clues to protecting them in the changing conditions of our planet, says Allen.

The recovery of humpback whales from the brink of extinction is an extraordinary success story in a world where more and more animal species are disappearing. Recovery began when commercial whaling became illegal starting in the 1970s.

The population, which collapsed to a few thousand individuals, is now estimated to be around 120,000–150,000. On the other hand, it is only about half of the number that was killed in the 20th century alone before hunting bans. Humpback whales that thrive in coastal waters were easy prey for the harpoon.

Even if whalers are no longer a threat to the stocks’ recovery, their strengthening is still not guaranteed, the researchers warn. The giants of the seas are now required to adapt to climate change, which is eroding ecosystems, both in their feeding and breeding areas.

If sea level rise and changes in water salinity reduce too much the food available in Arctic and Antarctic waters, the humpback whale will not be chubby enough when it starts to reproduce. One whale needs at least two thousand kilograms of food per day for four months.

At the other end of the journey, the water in shallow sea areas is becoming warmer than what humpback whales are used to in their breeding areas. A US-Australian study published in Frontiers in Marine Science in May threatens to do so during this century.

_The program tells about the CETI project, which tries to use artificial intelligence to find out what whales are talking about._