Ancient Baltic Finnish mythology is mocked in the popular new spirituality. My own archmyth may require always putting on the left sock first or bouncing the ball Four times before the game.

There are many interpretations of the meaning of the rainbow in all cultures of the world.

Although the myth of the treasure buried at the end of the rainbow, which was widespread in the early Middle Ages, is probably the most familiar now, the rainbow is most commonly thought of as a bridge between the here and the afterlife, between the worlds of humans and gods.

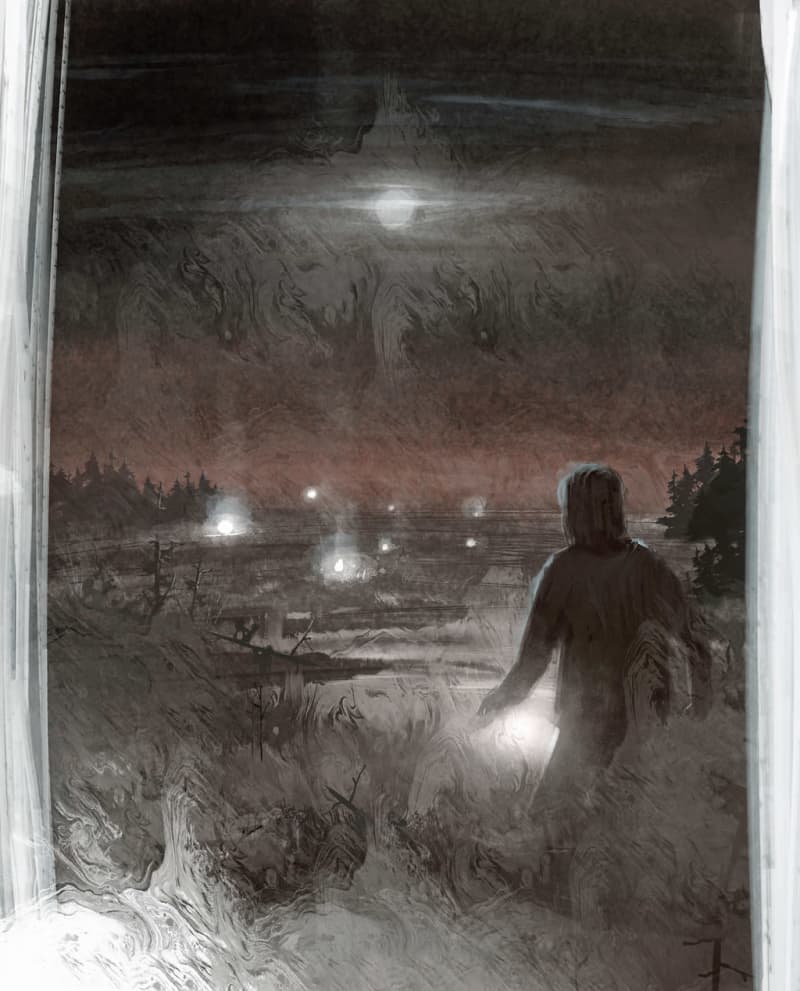

In old Estonian folk beliefs, the rainbow meant boredom and death, and a double arc reflected in the sky was known as a particularly bad sign.

It would be easy to smile at the neighboring people and consider them gullible, but how many of us Finns do not know or have even tested the snail’s ability to tell with its horns whether there will be rain tomorrow?

Or wouldn’t you have heard that rowan does not bear two large berry crops in the fall and a lot of snow the following winter? Or guessed from someone’s grumpiness that he got up on the wrong foot in the morning?

It may not be very serious, but something in us humans has caused even these old people’s ideas to be passed on from one generation to the next. New mythical concepts are also emerging all the time, and life would be gray without them, says Marju Kõivupuu.

– People tend to mythologize all kinds of things, including people who stand out from the rest. In Estonia, President Lennart Meri, among others, has become a mythological figure in his own way, Kõivupuu stated at the launch of his book in Tallinn.

On the one hand, myths are stories about where the world, people, animals and plants originated, or where diseases and their cures originated.

– In a way, they are the most sacred texts. If you think about the Bible, it starts with a myth: God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh, Enges quotes.

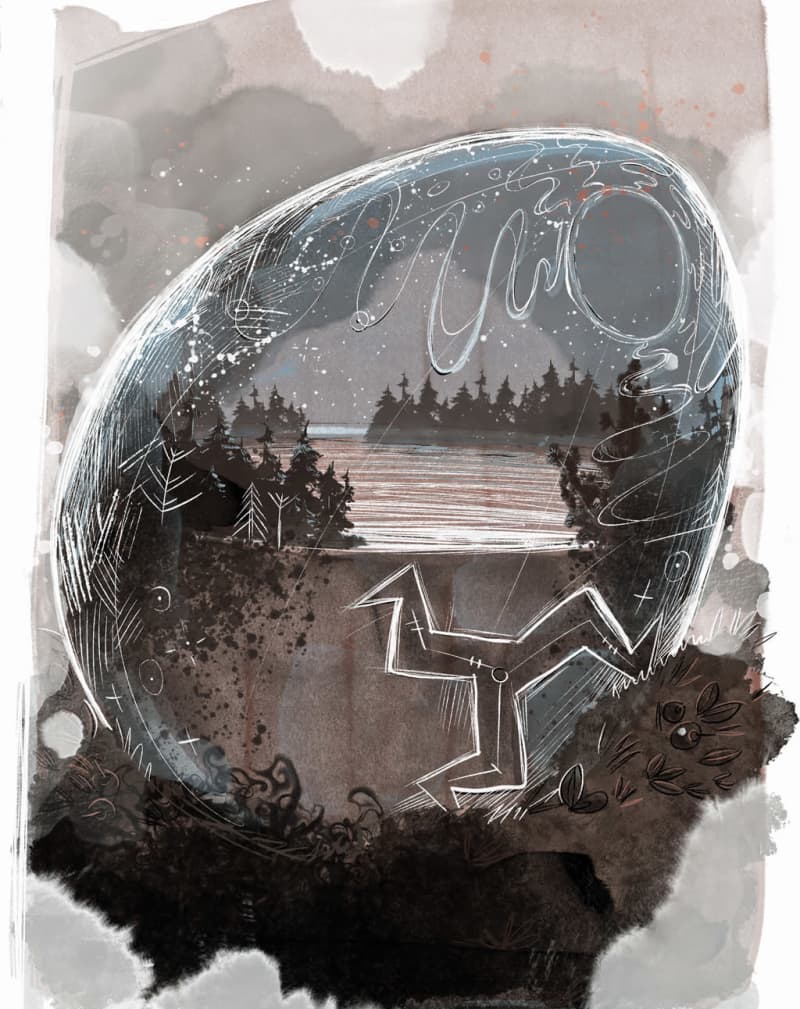

According to him, birth myths are mostly very international in terms of their basic ideas, they have just adapted in different ways to different cultures, such as the idea that the world was born from a bird’s egg.

– That concept is known in South America and Egypt as well as among the Finno-Ugric peoples. It’s hard to say why so many cultures have come to think of the egg as the beginning of the world.

On the other hand, a myth can be any unexplained cause-and-effect belief-based thing – including beliefs related to everyday things such as the connection between the rowanberry harvest in autumn and snowfall in winter. Such a concept, called a myth, is often condemned as a delusion or a naive superstition, says Pasi Enges.

– In the case of these, the meaning is actually the opposite of the actual folk belief. There is no supernatural element, being or force influencing things.

According to Enges, the question may rather be about an experience that has come true often enough, about a mystically colored relationship with nature and, in modern times, perhaps also about romanticizing the natural environment.

If someone thinks that such concepts have disappeared from today, that is of course not true, says Enges, like Kõivupuu.

In everyday life, a person can, for example, avoid stepping on the border of street tiles. He doesn’t know the reason, but thinks that it’s best not to step, because he thinks that something bad will follow.

– If people are asked if they believe in such a thing, they say \”no\ but we act accordingly and it matters. \”Better to look than to regret\ explains Enges of the background of the thinking.

There is no known culture in the world that lacks transcendence. This human tendency towards myths has been explained in many ways, says Pasi Enges.

– It has been assumed to arise from the subconscious and to be species-typical for humans. For others, culture and environment are more influential. Maybe it involves both.

What about the double rainbow that many Estonians noticed before Estonia sank? Which could they see what they saw: a cause of destruction or an omen that had no cause-and-effect relationship?

– Yes… Actually, it cannot be said that there is only one explanation for such things. Mythical images and ideas about how things are connected to each other are not a logical system without gaps.

Rather, it is a network with contradictions and antagonisms, Enges answers.

– People’s perceptions are linked to time and place, and some are communal, some are individual’s, based on their life experiences, education and growing environment.

What did the cultural circle of the Baltic Finns believe in two millennia ago, when Christianity was taking shape far away in Judea? Clues have been sifted from folk poetry among the influences of Christianity.

– There is quite a lot of indirect information about pre-Christian religion, but there is direct information only from the time when it had already become syncretistic, says Pasi Enges.

In syncretism, religions change little by little due to the influences they receive from each other. Even in Finland, faith was not changed all at once, but Christianity gradually seeped first from the East and then from the West to become part of the ancient faith.

According to Enges, the local faith probably had millennia-old mythical ideas about, for example, a creator god, but on the other hand, some deities of the forest and water could have been Catholic saints in the beginning.

– They had been misunderstood a bit, and their Christianity had kind of disappeared from view, Enges explains.

The synchronistic transition period between ancient faith and Christianity can be compared to present-day Estonia and Finland, where membership in the church is constantly decreasing and many are looking for a personal relationship with the afterlife from the so-called new spirituality, including its spirit beings.

In the 2019 Gallup Ecclesiastica survey by the Church Research Center, especially more and more young adults were of the opinion that there are invisible worlds and beings that also influence the real world.

About two-fifths of men aged 15–29 believed so, at least to some extent, and slightly more of women. There was also growth in the thirties.

– Even though we are in a Lutheran country, some part also believes in soul wandering. Practically lived religion or beliefs are different from what the church and the state are committed to, at least formally, comments Pasi Enges.

The fact that tracing the pre-Christian worldview is difficult and getting a complete picture is hopeless does not prevent researchers from doing their best.

– The carnival-sized poems in the archives are indeed a central source. Baltic Finnish mythology has actually been reconstructed specifically through them, says Pasi Enges.

Additional information has been obtained from archaeological finds and ritual descriptions, and with linguistics it is possible to create etymologies that go back thousands of years, he lists.

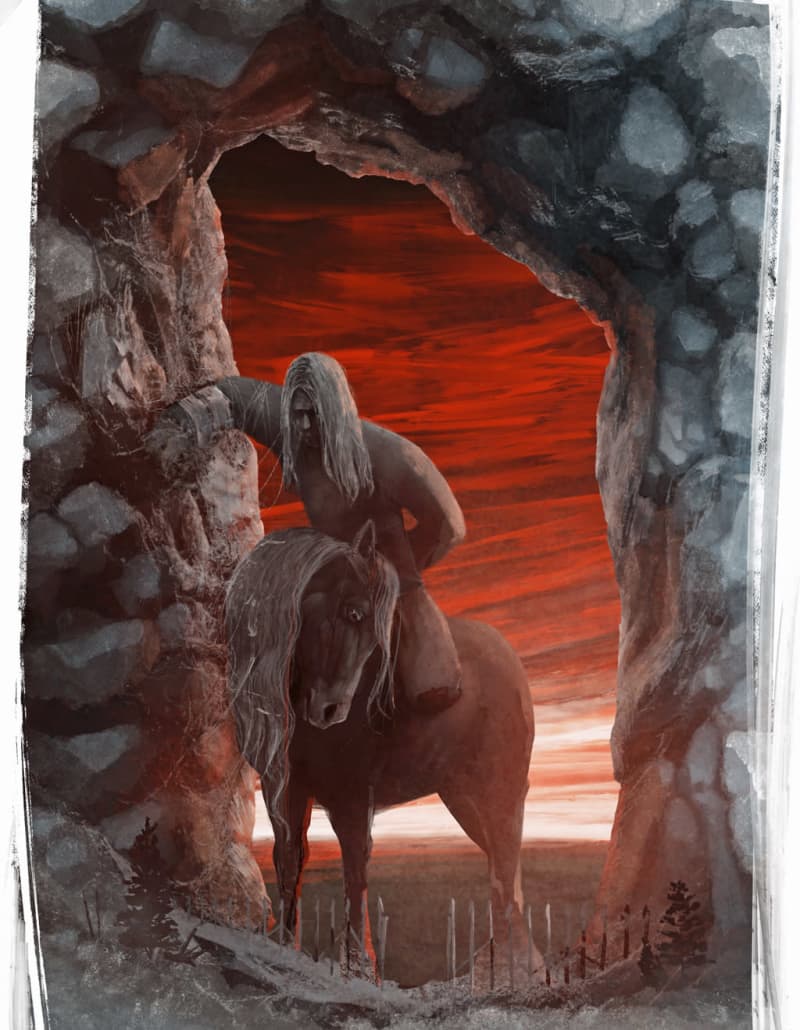

It pays to talk specifically about the worldview, because talking about religion can lead your thoughts astray. Practicing faith meant something completely different than in today’s occupation religions, where rituals have specific times and places.

Of course, there were groves of rice, image cliffs and places of worship before, but appeasing religious creatures, asking them and giving gifts in return were also an integral part of everyday life. The goal was practical: getting resources from nature, avoiding dangers, ensuring existence.

– Reciprocity with nature may have been lost, but if you think about these new trends, forest yoga or hugging trees, you can think that the old-fashioned relationship lives on to some extent, says Enges.

– Lönnrot’s goal was specifically to reconstruct a pre-Christian epic, which he dated to roughly a thousand years ago, but he himself later found out that he himself had created the epic from poetic materials, answers Pasi Enges.

It is known from Lönnrot’s working methods that he really tried to present \”old Karelian poems from the ancient times of the Finnish people\” according to the subtitle of the Kalevala.

– He deliberately eliminated Christian ingredients from, for example, spells. Kalevala is thus in a way paganized, if you use an outdated term.

Already in the 19th century, it was disputed whether the poems of the Kalevala were historical or mythological. At that point, the mythological interpretation clearly won: it was thought that Väinämöinen and the other characters in the Kalevala were divine beings, Enges says.

In the preface to the second edition of the Kalevala, Lönnrot stated that he could have made seven different Kalevalas from the same materials, depending on how he would have arranged the poems and what kind of plot he would have developed in the book.

– However, the public and researchers thought for a long time that Lönnrot had succeeded in reconstructing an ancient epic similar to the *Iliad* and *Odyssey* or other epics of civilized nations, says Pasi Enges.

Although the Kalevala is Lönnrot’s creation and there are only hypothetical ideas about the birth time of the folk poems, according to Enges, there is quite a consensus about the long age of the Kalevala meter. The familiar trochee was born about two thousand years ago at the latest, and both archaeological and linguistic studies seem to postpone the beginning even further.

Mythical images also tend to change very slowly, says Enges.

– Even though culture changes, fundamental images still want to remain and follow people from century to century. They just adapt to new conditions. In that sense, one can well think that the folk poems collected in the 19th century contain material that is inherited from two millennia ago.

In the 19th century, the Finns and Estonians, who joined the ranks of nations, needed their *Kalevala* and *Kalevipoeg* epics to prove their ancient roots and uniqueness. Marju Kõivupuu says that as a folklorist, she still comes across similar thinking from time to time.

– Estonians have always wondered who we are. It’s terribly important, and sometimes people get offended when you explain to them that something considered our own has come from somewhere else in one way or another and passed through a filter to us.

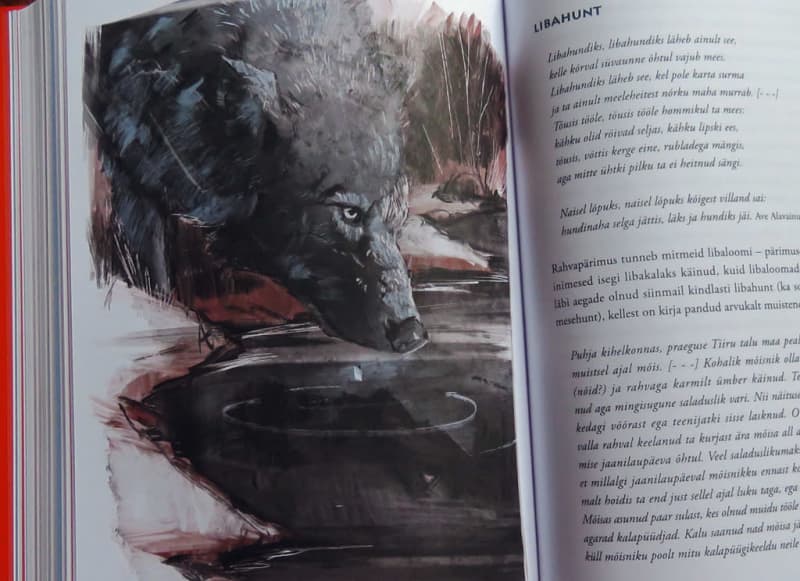

Globalization, however, also takes the flow in the other direction. Although the interest in mythology is still great, both as entertainment and as a new spirit, Estonia’s traditional kratti, näkki and various kinds of holders have become increasingly foreign in their own country.

Kõivupuu answered that with his book \”Estonian Mythology for Beginners\”.

– My book has a mission. Archives give researchers more and more material, but young people mostly know mythological characters from foreign films, computer games and fantasy literature. They may have been left with the impression that their own culture has nothing mythical to offer.

In addition to scientific publications, Estonia also needs more popularization, bold interpretations for ordinary readers of how people have seen the world around them, says Kõivupuu.

In Finnish folklore, there are gods and guardians, holiness is found in the forest