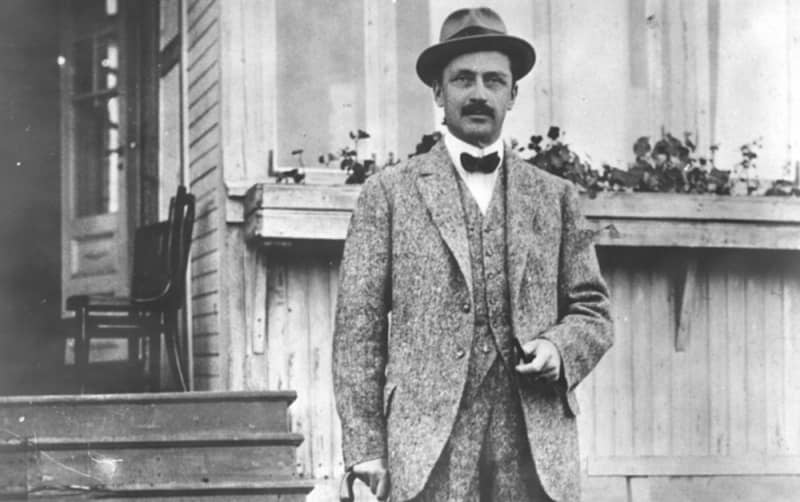

Mannerheim is probably the most mythical figure in Finnish history. This exceptional status did not come about by chance, but the cult of Mannerheim’s personality began to be built up immediately after the Civil War, says historian Tuomas Tepora.

– Finland is an interesting democracy. We have a tendency to put characters on a pedestal.

– Mannerheim was not only a real person but also a fictional character. Finns have a very strong and contradictory image of him.

A man few people knew. When the Finnish Literature Society organised a collection of memoirs on Mannerheim in the 1960s, the results were meagre. Someone had perhaps once seen Mannerheim in the street and the story ran in the family as a precious memory. However, the memories did not provide any real insight into their subject.

According to Tepora, distance is an essential part of cult building. It’s easier to worship someone you don’t know – a phenomenon familiar from the pop world.

– President Kekkonen is a very different character in terms of his imagination capacity, folk-like, Finnish-speaking.

However, Horthy and Piłsudski were also absolute rulers. Mannerheim just almost.

– For the Mannerheim cult, it is essential that he did not become a politician, Tepora says.

The general of White Finland was also tried to become the country’s political leader. According to Tepora, right after the civil war, Mannerheim’s inner circle began to build a personality cult around Mannerheim. Governor Mannerheim toured the provinces and participated in the one-year celebrations of the War of Independence, where he performed among the protectorate residents, lots and children.

If it had been otherwise, Mannerheim might well have become an autocrat like Horthy and Piłsudski. At least parliamentarism and democracy would have taken a step back, Tepora thinks.

– Mannerheim’s statues would probably have been erected during his lifetime.

Instead, Mannerheim began to be constructed as an external savior, a mythical figure above politics.

The Reds also built the Mannerheim Cult

At the same time that white Finland was putting Mannerheim on a pedestal, the other half of the nation saw him as the devil.

According to Tuomas Tepora, in terms of building a personality cult, it is essential whether we operate in a free, democratic society or a dictatorship. In today’s Russia, criticism of Putin leads to a prison sentence or worse. A hundred years ago, it was possible to criticize the leader of the party that won the civil war in Finland.

– Dictators are often associated with the concept of a cult of personality and for them it is a tool of political control. In democracies, the situation is much more contradictory. Counter-images, for example mocking Mannerheim, also play a key role, Tepora explains.

For the Reds, Mannerheim was a pitfall. According to Tepora, he gave a face to the defeat of the civil war and the disaster of the prison camps. Among other things, Mannerheim was said to have visited prison camps. Often, something cruel and demonic was attached to the character in the stories.

Although the stories were not true, they also built the Mannerheim cult.

– It tells about how central Mannerheim was also in the eyes of the losers.

According to Tepora, the reds were even able to pay off fish debts a little with the stories emphasizing the evil connected to Mannerheim.

Towards the end of the 1930s, the left’s attitude towards Mannerheim began to take on new shades. The SDP had become the regent’s party and the position of power softened the attitude towards Mannerheim.

An even greater change took place with the Winter and Continuation War. Let’s talk about the spirit of the winter war: the common enemy forced to forget the confrontation of the civil war. In the eyes of the left – or at least some – the white general also emerged as a marshal uniting the entire nation.

In the extreme left, the lahtari image remained tenacious.

– The fact that Mannerheim was the commander-in-chief of the allied army of Nazi Germany is not as big a sin in the far-left tradition as the events of the civil war, says Tepora.

The huge symbolic difference between the White General and the Marshal

There were several concrete manifestations of the Mannerheim cult and they changed as times changed.

The central object of the cult in the initial phase were the celebrations of May 16. They commemorated and recreated the victory parade of the whites led by Mannerheim.

Exploiting children is a popular and effective means of propaganda. The builders of the Mannerheim cult also saw children as fertile ground for their message. The children performed at parties organized in Mannerheim’s honor, Mannerheim had adventures as a hero in children’s books, and the little lot was educated by the power of Mannerheim’s example.

Public space is also a central object of strengthening the cult. Already in the first years of independence, Mannerheimintei and streets could be passed in Loviisa, Mikkeli, Porvoo and the villa town of Kulosaari. Mannerheimintieta was first planned for Helsinki in the mid-1920s, but the project was not realized until the war year 1942 – Mannerheim celebrated his 75th birthday at that time.

However, perhaps the most central object of cult building and also of controversy were the statues.

Tuomas Tepora goes through numerous statue projects, the first of which started already in the early 1920s. Mannerheim himself had a mixed attitude towards statue projects, knowing that good manners did not include erecting a statue of a living person.

The first statues would have represented a white general and their wooden men were veterans of the War of Independence.

However, none of Mannerheim’s statues were erected before the Second World War.

Indeed, the statue projects were revived after Mannerheim’s death in 1951. In Helsinki, the statue project was revived only two days after the news of his death. Also in Tampere, the argument about the statue that started before the war continued. Statues were also planned for Seinäjoki, Lahti and Mikkeli.

In the statue disputes, the front line ran between the right and the left, however, so that the moderate left could accept a statue depicting the old Mannerheim from the Second World War.

– The symbolic difference between the white general and the commander-in-chief of the Second World War is absolutely huge, Tepora sums up.

The white general divided, the marshal united the Finns.

Touching a statue unleashes uncontrollable forces

The question of the statue’s location brought its own twist to the statue disputes. For example, in Tampere, the statue was planned for the city center, where a pedestal was already erected for it. However, after the war, political trends had changed and the statue of the white general ended up in a remote forest on the eastern edge of the city.

In Mikkeli, the location of the statue has been twisted twice. First, it was erected in Suur-Savo square, from where the statue wanted to be moved to its core center in Mikkeli market at the beginning of the 2000s.

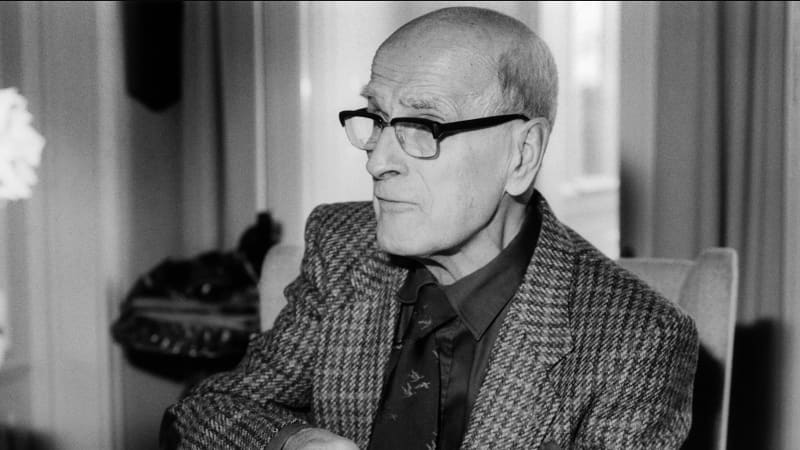

– Ehrnrooth’s role in building the Mannerheim cult was central after the war. In a way, he conveyed Mannerheim’s will from beyond the grave, says Tepora.

Surprisingly, the knights opposed moving the statue to a much more central location.

According to Tuomas Tepora, the background was influenced by the dispute in Helsinki a little earlier about Mannerheim’s equestrian statue and the contemporary art museum Kiasma.

In a highly publicized dispute that was personified by Adolf Ehrnrooth, the foundations first objected to moving the equestrian statue out of the way of the museum building, and finally the entire museum building. After this, it would have been strange if they had advocated moving the statue in Mikkeli.

However, according to Tepora, it was a bigger issue than just negotiation tactics.

– Knights and the Heritage Foundation considered that the statue that had stood in Suur-Savo square since the 1960s had sanctified the place and moving it would have been sacrilege.

The attitude reveals what kind of meaning Mannerheim has for some Finns.

– Mannerheim’s statues are like totems, holy figures, touching which may release forces that are difficult to control.