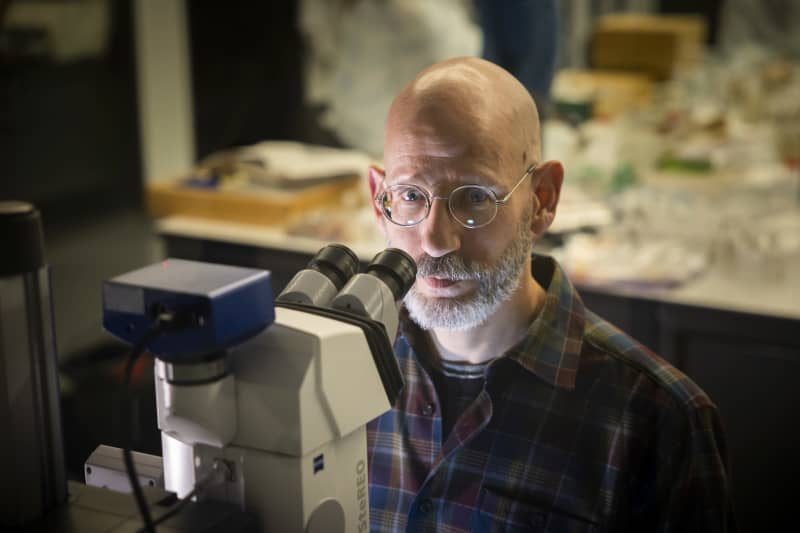

“When we talk about global population decline, I would put insecticides at the top of the list,” says Professor Colin Favret of the University of Montreal. The city is hosting the International Conference on Nature.

The Quebec woods overlooking the lake look familiar to Finns. The forest’s contours are outlined by birches, spruces, a variety of pines and, of course, Canada’s iconic maple trees.

Just over an hour’s drive from the metropolis, you’ll find a winter silence broken only by human footsteps and the loud flapping of bird wings that startle them into flight.

It’s just that you won’t see any other animals here today. Beavers hibernate under the ice, coyotes scare people and foxes don’t show up, even though they’ve left their greetings on the slope.

Many insects overwinter in the slush layer under the thin snow. At the weekend, according to weather forecasts, it will snow more and the forest will take on its winter veil.

As the nature meeting is going on in the city center, it is time to remind about the importance of science in understanding nature.

Because of this, the University of Montreal has extensive plant and insect collections that tell stories about nature and the people behind the research.

Modern world threatens insects

A large meta-analysis published in 2020 that combined 166 long-term studies reported that the number of insects in the world fell by 24 percent in two decades.

Studies have given different estimates of the scale of insect loss. There are significant regional and ecosystem-specific differences in development. Still, the big picture tells us that insects are in trouble in a changing world.

There is a long list of estimated reasons for the loss of insects: for example, the loss of natural habitats, the cultivation of the same plant in a large area and climate change.

One rises above the rest on Favret’s list.

– When we talk about the global dwindling of populations, I would put insecticides at the top of the list.

Goal number 7 of the Montreal negotiations deals with pollution: microplastics, light and sound pollution, heavy metals and also insecticides.

In the insect world, there are many nocturnal species that are especially disturbed by light pollution. They are used to the night, and light pollution takes it away, the moths are left spinning around the lamps and exhausting themselves. As a result, they may not find food or a mating partner.

Currently, the goal of the UN Nature Conference includes the need to reduce all pollutants to the level that they are not harmful to biodiversity and ecosystem services.

The registration of pesticides in the agreement text is still in square brackets, i.e. under negotiation. The countries continue negotiations on the amount of toxic reduction, for example halving or other significant reduction.

Quebec’s missing bumblebee

According to Favret, the issue of insecticides is very difficult, because there are two sides to the coin.

– We need plant protection agents to produce food, but especially poisons that remain in the environment for a long time lead to terrible consequences for insects.

An example of this is neonicotinoids, which were also used in Finland in rapeseed and sugar beet cultivation until the EU banned their use in field cultivation in 2018.

Neonicotinoids were noticed to accumulate in beehives, where the long-lasting toxic load especially taxed the offspring of the communities.

Concern for pollinators has united people around the world. Without the ecosystem services they provide, the cultivation of many food crops would be practically impossible.

The university’s collection contains at least one example of a pollinator that is no longer found in the Quebec grasslands. The *Bombus affinis* bumblebee is classified as extremely endangered. Populations of the species have shrunk by 87 percent in its historical range.

In 2017, the species became the first bumblebee classified as endangered on the North American continent.

You cannot predict the future of nature without knowing its history

– We cannot understand nature without understanding what everyone does in the ecosystem. Animals, plants and fungi all play a role, and the more diverse the ecosystem, the more balanced it is, says Colin Favret.

Since Favret’s bread and butter is insects, we begin our review of natural history through insects.

Humanity has identified more than a million species of insects, but according to estimates, the actual number is 5-10 times higher.

– We are only at the beginning of cataloging these species. When a species becomes extinct, it is dead forever. We need to know what lives on our planet so we can protect it, says Favret.

The scientific measurement of endangeredness requires information on how many individuals of the species have been observed historically compared to today. You have to know nature’s story in detail if you want to recognize the nuances of today.

The future of nature cannot be predicted without knowing its history. A person is an integral part of both.

Based on this statement, Colin Favret wants to give the UN, which decides on the future of nature, one piece of advice in particular.

– Biodiversity should not be a political issue that divides us. It should be something that unites us, as long as we evaluate the benefits and harms of our actions.

Collections about life, adventure and death

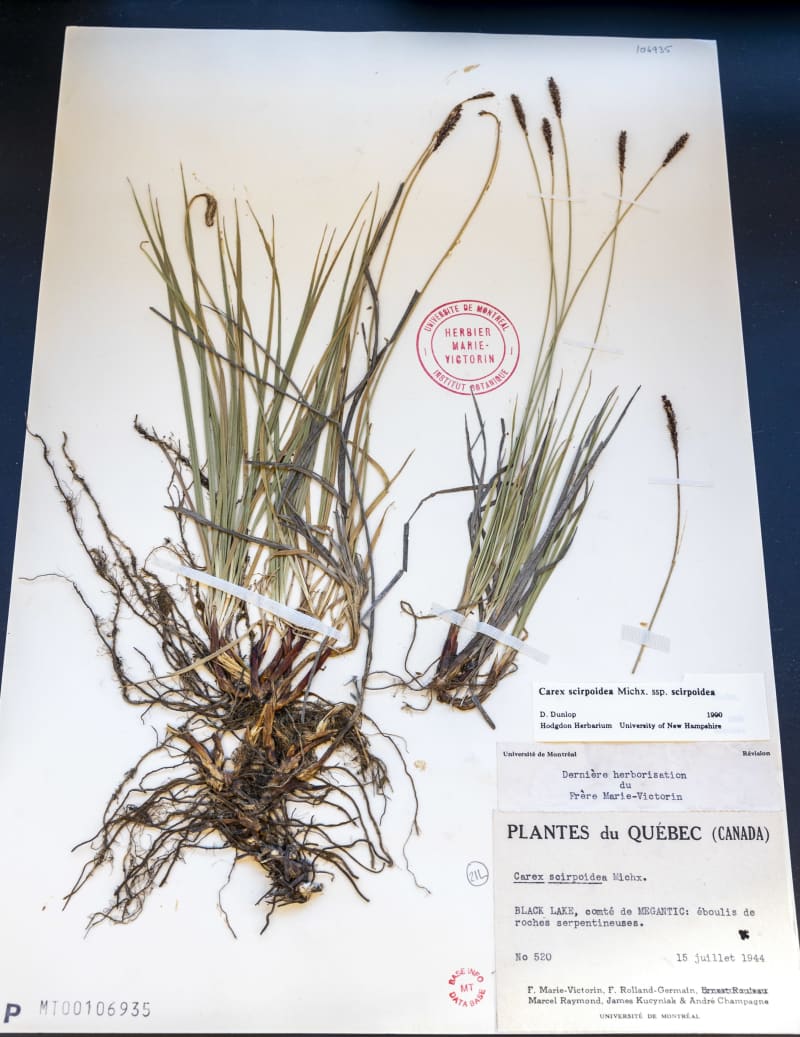

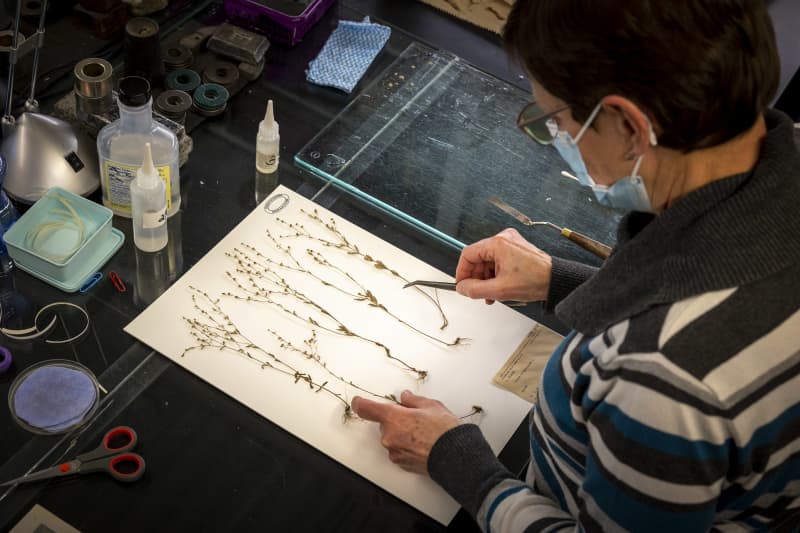

The university’s plant collection comprises approximately 700,000 specimens. Because there are so many samples, no one knows exactly what all can be found in the collections.

Pressed and dried samples can be preserved for centuries, at least if they avoid pests. That’s why the room filled with huge filing cabinets is cooler than the other spaces of the biodiversity center.

The collection is now being digitized by volunteers. Approximately 7,000 samples can be photographed per year. At this rate, the collection would be available to everyone on the internet in about the next century.

However, there are about the same 7,000 new samples every year, so without a significant increase in funding and the hiring of labor, it will take forever to digitize the collection.

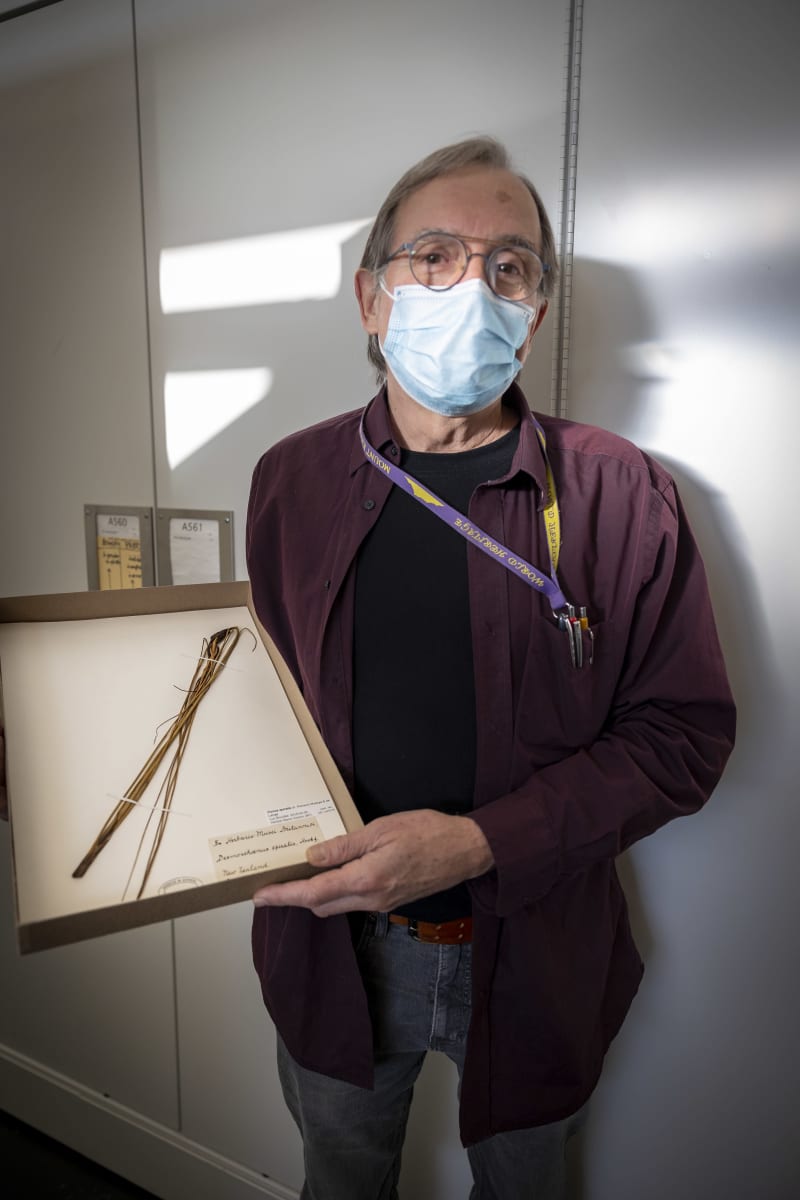

Few would believe that pressed plants could tell about life, adventure and death, but the collection has crown jewels that are also closely connected to the history of mankind.

The collection includes not only Marie-Victorin Kirouac’s first plant specimen from 1908, but also the last, dramatic collection piece from 1944.

The botanist died in a car accident while returning from a collecting trip. The samples were preserved and they were carefully handled, respecting the life work of Marie-Victor Kirouac, as a symbol that human life is transient, nature is ancient.