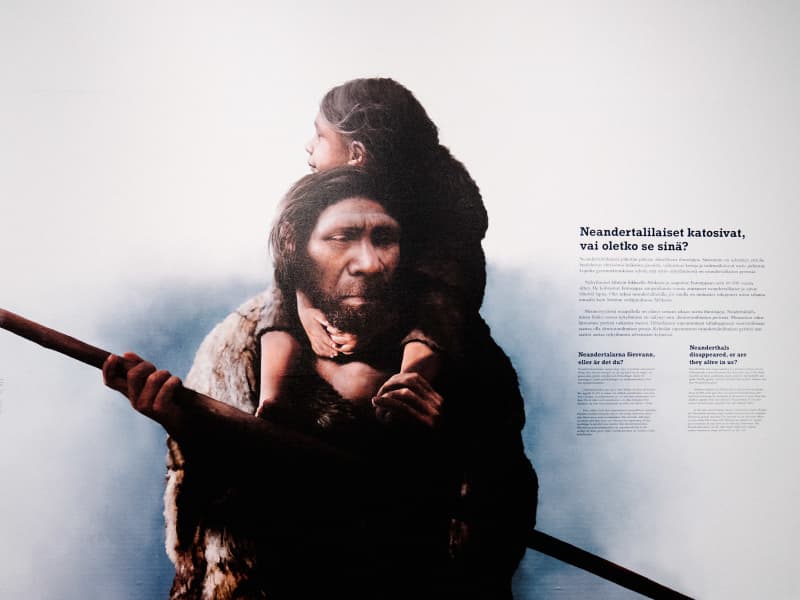

A family was found among the Neanderthals for the first time: a father and teenage daughter and other relatives lived in a Siberian cave. What they inherited opens a new window into the way of life of our cousin species.

Genetic research produces more and more detailed information and their interpretations of our extinct cousin Neanderthal man. In the latest research, we can trace the Neanderthal family and lineage for the first time.

In the Chagirskaya cave in Southern Siberia, at the foot of the Altai Mountains, representatives of different human species lived in turn and, who knows, at the same time – Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern humans. Neanderthals lived there about 54,000 years ago.

Never before has the genome of so many Neanderthals been sequenced in one study.

Chagirskaja cave in itself is a very familiar and rewarding place for researchers. Researchers from the Russian Academy of Sciences have been excavating there for 14 years.

More than 80 fragments of Neanderthal bones and teeth have been found in total. There are few assemblages of Neanderthal finds in the world.

A lot of tools and remnants of food have also accumulated.

Even the tools bear witness to the roots in Europe

The exceptionally extensive genetic material revealed that the inhabitants of Chagirskaya were more closely related to their fellow species living in Europe at that time than to the Neanderthals who previously lived in Denisova Cave in Siberia.

Denisova Cave is only a hundred kilometers away, Europe is thousands of kilometers away, but the Neanderthal finds in Denisova Cave are tens of thousands of years older than those in Chagirska.

The petrified toe found in Denisova has proven in previous studies that Neanderthals migrated to the Altai at least 120,000 years ago. The inhabitants of Chagirskaya must have been the heirs of a much later wave of migration.

Their tools also prove that. Above all, they resemble the handiwork typical of the Neanderthals who lived in Germany and Eastern Central Europe.

The raw material of the tools, on the other hand, supports the idea of \u200b\u200ba recent study about the solid connections of the inhabitants of the neighboring caves 54,000 years ago. Although the material comes from tens of kilometers away, it is the same in the tools of both caves.

When the gene analyzes continued, the researchers were completely surprised. A father and his teenage daughter were found among the inhabitants of the cave. This kind of close kinship had never come up in Neanderthal studies.

They had half the same genetics, so they could have been siblings as well. However, each of them had their own mitochondrial DNA, which proved that they had different mothers. Mitochondria are inherited only from the mother.

It is believed that new members will join the family as the investigations continue. Only a third of the cave has been excavated, and less than a quarter of the remains that have already been found have been analyzed.

Two of those already identified were close relatives of father and daughter. A middle-aged boy and an adult woman were relatives of the man’s second generation, so possibly a young cousin and an aunt or even a grandmother.

No Denisovan genes were found

There were also other relatives in the group. This is evidenced by the fact that many mitochondria have the same abnormality as the teenage girl’s father.

Heteroplasmy, where two types of genes are mixed, usually disappears in a couple of generations. From this, the researchers concluded that the inheritors of the abnormality were alive at the same time.

On the other hand, no signs of intimate relations with the Denisovans were found, although they probably moved in the same area at the same time. There is direct evidence of relationships from an earlier time: 90,000 years ago in Siberia, that is, a woman whose mother was a Neanderthal and whose father was a Denisovan.

The first Neanderthal genome was opened at the Max Planck Institute in 2010. Thanks to it, Svante Pääbo, the creator of the field of paleogenetics, is a recent Nobel laureate.

The latest study, in which Pääbo also participated, almost doubles the number of Neanderthal individuals analyzed.

From the genes, it was now possible to find out, among other things, the size of Neanderthal groups. In the past, it has been evaluated from the signs and footprints of living in the campsites. The size of the groups increased to 10–20 people.

At the same time, the idea arose that the entire Neanderthal population in Siberia was very small, perhaps only a few thousand people.

At least half of the women changed communities

One important observation about Chagirskaia was the very low genetic variability of the community.

There was much more inbreeding than in any known modern human community before or now. The research result corresponds to the state of the gene pool of animal species on the brink of extinction.

It supports considerations according to which erosion caused by inbreeding may have been one of the factors that contributed to the extinction of the Neanderthals.

However, the Neanderthal lilac groups did not live a completely isolated life from each other, especially not the women. Mitochondrial DNA inherited from the mother turned out to have much more variation than Y chromosomes inherited from the father.

According to the modelling, the genetic diversity of mitochondrial DNA is so great that it could only be reached if at least half of the women were born from another group. According to Skov, even all women could leave their birth groups.

A baby’s tooth is strange

A decade ago, his research group analyzed the DNA of Neanderthals from a Spanish cave and obtained similar results regarding the variability of the inheritance received from the mother.

He is particularly concerned about the baby’s milk tooth and two permanent teeth, whose DNA proves that they belonged to the same man.

– It seems to me that his community either lived in the same place for a very long time or returned there often, says Wragg Sykes.

In the Chagirskaya and Okladnikov caves there are not only remains of humans, but also a lot of pieces of mountain goats, bison and horse bones from the short period when Neanderthals lingered in the caves. \”Short\” in the long history of the Neanderthals means no more than a couple of thousand years.

Large animals were the game hunted by the Neanderthals, after which they traveled along the Charišjoki valley. Researchers think that the caves located on the riverside were some kind of seasonal camps along the annual migration routes of prey animals.

– The hunt offered the groups an opportunity to get to know each other. It was hardly agreed in advance, but it became an opportunity, says Laurits Skov.

According to him, it is highly unlikely that the community had returned to bring their dead to the same caves at different times, so the members of a small family unit most likely perished at the same time.

What killed them? Probably hungry. Maybe they just had bad hunting luck. Or perhaps their fate was met by a fierce Siberian winter storm, Skov says.