Permits have been granted for deep-sea excavation mapping. Finland has joined the list of countries calling for more research into the environmental impact of mining.

July 9 is a significant day for the oceans. It will mark the end of a two-year period in which the International Seabed Authority (ISA) must finalise regulations on deep-sea mining.

That will not happen.

The 36-country ISA Council met in Jamaica in March, but the package was not finalised. The next meeting of the Council will take place a day after the deadline, with the organisation’s General Assembly starting at the end of July.

ISA has granted a total of 31 permits for mapping the possibility of deep-sea excavations. No utilization permit application has been submitted yet.

Such a thing may land on the organization’s table soon. The Canadian The Metals Company is planning that, among other things, rare earth metals would be able to be raised from the seabed as early as next year.

Currently, the operation is regulated by the general Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Car wrecks and a team of investigators in resistance

Many are concerned about the effects of mining on the oceans. Microsoft and Google as well as car manufacturers BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo have announced their opposition to the use of metals raised from the bottom of the sea.

– It seems that we are going a bit too fast towards mining without having done the relevant studies on whether this kind of activity is ultimately profitable, says Kaikkonen.

Twelve member countries of the ISA are calling for a pause in inches. Germany, Spain and a number of South American and Pacific countries want more research into the environmental effects. Mäkelä says that this group also includes Finland.

The seabed organization has plenty of work to do in areas other than mining’s environmental impact. For example, it has to decide how the economic benefit from the seabed metals, which are considered the common heritage of mankind, will be shared.

Up to 40 per cent metals in nodules

Seabed mining is mainly about nodules, metal-rich deposits. They have been created over millions of years and are estimated to be at the bottom of the oceans, at depths of kilometers up to hundreds of billions of tons.

There are a few nodules at the Geological Research Center in Otaniemi, Espoo. They are about the size of a new potato and surprisingly light.

Many of the metals are coveted by the battery industry, such as nickel, manganese and cobalt. The volumes are huge. A third of the useful resources of copper, which is important in electrification, is at the bottom of the sea, the rest on land.

Rare metals such as cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, gadolinium and samarium are also obtained from the nodules.

So there are two big issues in horizontal cups: on the one hand, the concern about ocean pollution, on the other hand, the possibility of raising metals that are essential for combating climate change.

– This has been thought about for 60 years, so it’s not a completely new thing. Technically, it is not necessarily easy, i.e. we just go and vacuum, but here there is pressure to get various metals to go green – either from land or sea areas, Vuori says.

Seabed regeneration

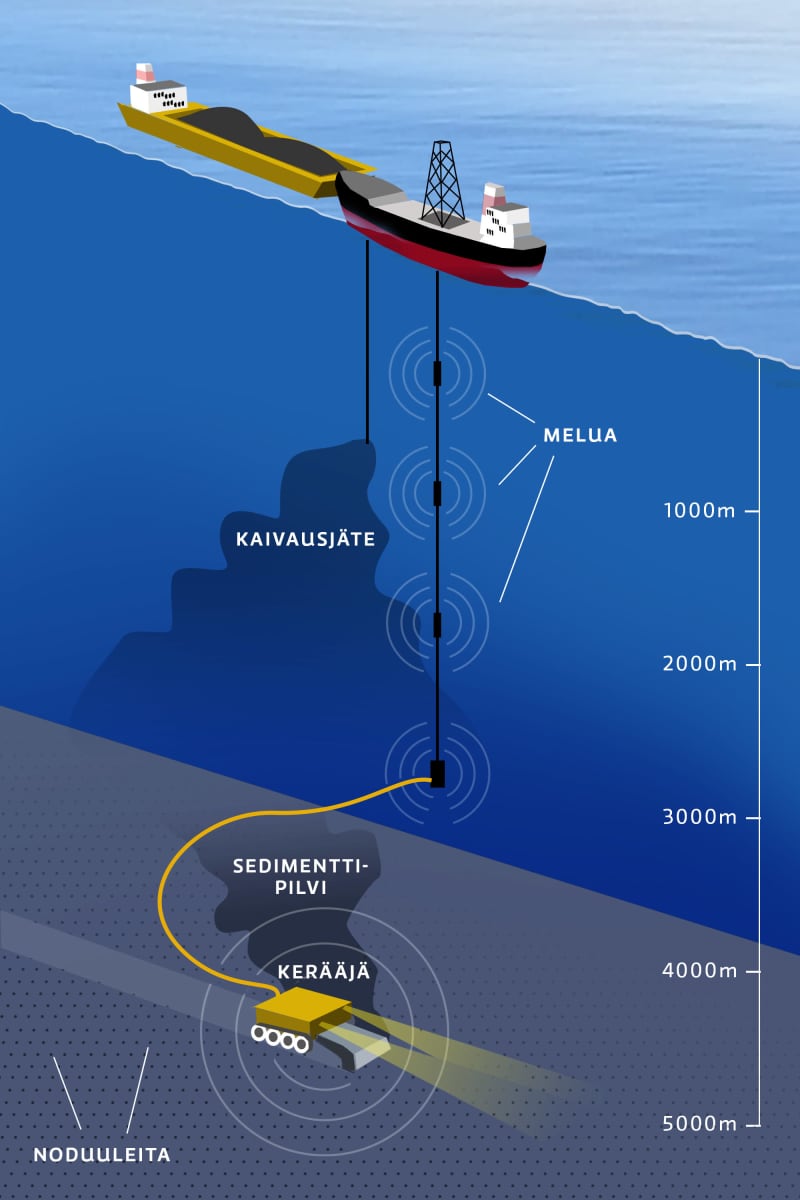

Deep sea mining is not about drilling. Current technology is like harvesting: a vehicle is lowered to the bottom of the sea, which collects and vacuums the nodules in the sediment. They are lifted to the surface with the help of pumps.

This is exactly what concern for nature is about. What happens to the loose sediment during vacuuming? How wide does it spread? What does it do to the seabed ecosystem? What are the effects of mining noise?

There are no answers to these questions yet.

– The nodules provide an attachment base for all kinds of organisms such as corals. When the nodules are removed, the habitat, which has been found to have a very high biodiversity, is completely removed, says Kaikkonen

The oceans are still a great unknown. In investigations carried out at depths of kilometers, completely new species of organisms are often encountered.

– Is it acceptable to go jogging in ecosystems with species that we don’t even know about. So let’s destroy something that we haven’t had the chance to know, Kaikkonen asks.

The need for earth metals may also change in the next few years when new battery technologies are developed. The Chinese battery manufacturer CATL recently announced that it will start installing sodium ion batteries in passenger cars.