In the summer of 1972, the eyes of the world turned to Iceland. On the first day of September, almost two months of chess crunching ended with one phone call.

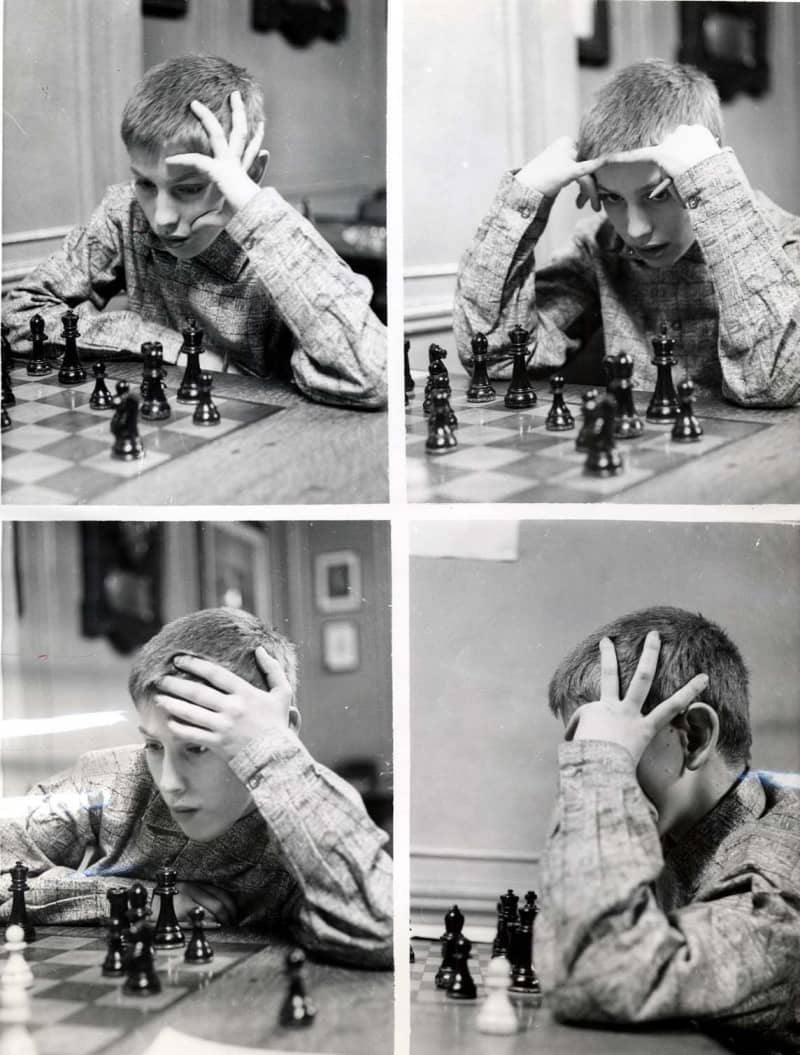

Mydans’ photo series was published in the well-known Life magazine. At the same time, it painted a picture of intransigence, which stretched even to stubbornness. Over time, the awkward nature became one of Fischer’s best-known trademarks.

For years, Fischer’s life had mostly revolved around chess. He won his first US championship at the age of 14 and by the 1960s had already played in European tournaments against the top players of the Soviet Union.

Superluapaus’ career went on a rollercoaster ride in the 1960s. Fischer sought to become a contender for the world championship match as early as 1962. He had won the Interzonal qualifying tournament in Stockholm with impressive numbers, but fourth place in the bachelor tournament was a bitter disappointment.

Considering the zeitgeist, it is quite possible that the Soviet players actually played fixed games. On the other hand, Fischer’s accusations gave a first taste of his paranoid and conspiracy-loving nature.

Fischer did not participate in the qualifying tournaments of the next world championship match at all. In 1967, he was seen again in the Interzonal tournament, from which Fischer retired in the lead midway through the tournament.

Petrosian, who was only turned as the last stone, ended Fischer’s incredible 20-game winning streak, although he lost the match by a clear final count.

The goals are Cold War heroism and a big wallet

Three years had passed since the first step on the surface of the Moon. The Soviet Union and the United States had taken fierce strides in the conquest of space and wanted to show their power to the other pole of the world.

For the Soviet Union, chess was also an important way to demonstrate superiority, and unlike the race to the moon, on the 64-square board, the Eastern Bloc was completely sovereign.

Soviet players had won all the world championships since the format came under the auspices of the World Chess Federation (FIDE) in the 1940s.

Even though the 1970s was a time of easing of superpower relations, it was undeniably clear that Reykjavík would be played for something other than the world chess championship.

Experts have believed that Fischer got an added boost from a kind of man-versus-machine setup: in chess, the Soviet Union had enormous muscle, and the grandmasters worked together to get at Fischer’s weaknesses.

Moka, surrender win, secret phone calls and intrusive cameras

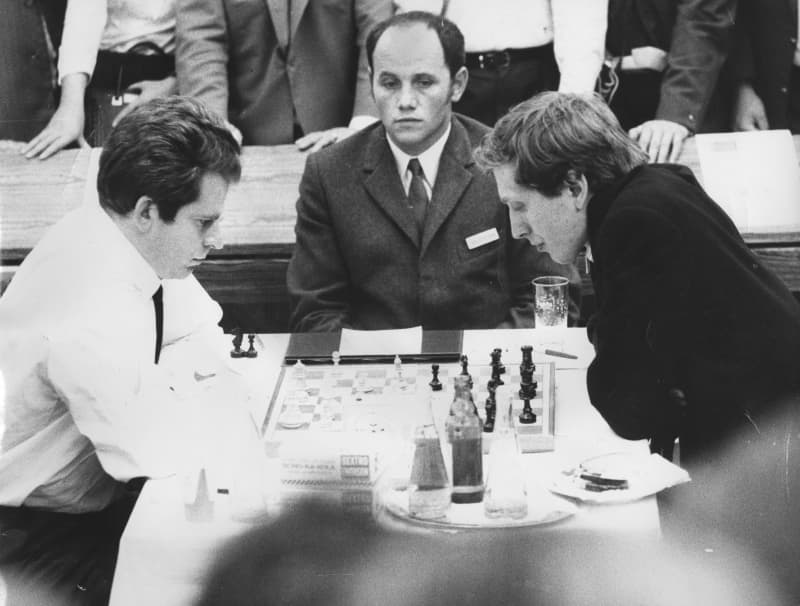

July 11 in Iceland: exactly at five o’clock Boris Spassky moves the pawn from in front of the queen to square d4 and starts the game clock.

2,300 people are waiting in the stands of the Laugersdalhöll arena. Fischer, who rowed and felted before the match, is not seen in the hall for nine long minutes.

Fischer is stuck in a traffic jam and soon rushes to the stage accompanied by applause, shakes his opponent’s hand, thinks for 95 seconds and plays the knight to the square f6.

To the surprise of the whole world, Fischer eats the pawn on h2 with a bishop, leaving his bishop stuck. The grandmasters in the hall can’t believe their eyes.

Over the years, the move has been analyzed again and again: maybe the transmitter switch to two pawns doesn’t lose outright, but Fischer seals his loss by fouling even later in the endgame.

For the next game, Fischer doesn’t show up, but gives Spassky a forfeit win and watches the flights back to New York. After the submission, Fischer receives another call from Kissinger, who apparently demands that the match be continued.

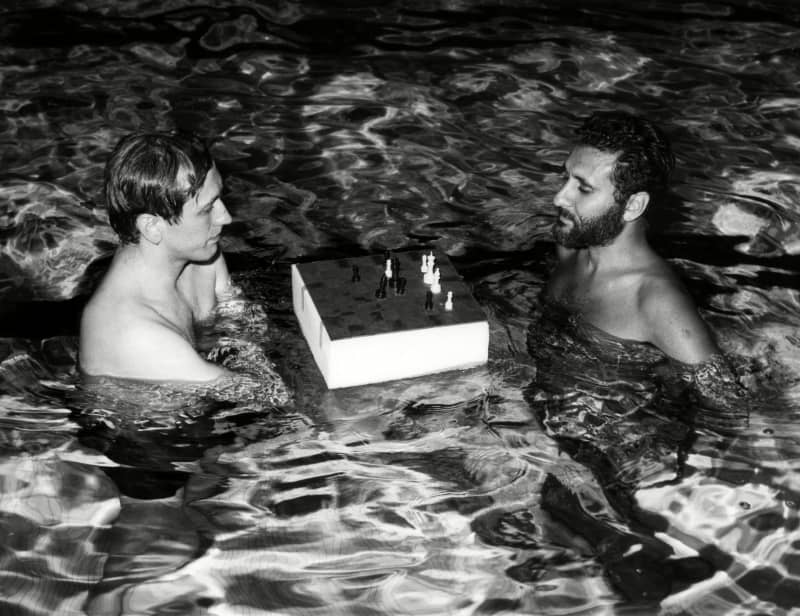

Spassky accepted Fischer’s wish to move the rest of the games from the skull place to the back room, where table tennis was normally played.

For Spassky, this probably cost him the world championship, but for the world, it guaranteed the continuation of a unique match. The final reversal of momentum came in the sixth game, after which Spassky reportedly gave a standing ovation to Fischer’s skill.

Fischer eventually won the match sovereignly, losing only one of the remaining games. Eleven games were drawn, Fischer won six, and on the first day of September, Lothar Schmid received a phone call announcing that Spassky had conceded the match.

The Soviet Union’s hegemony on the chessboard was – if not completely broken, at least dented.

– But what happens next, now that Fischer is the world champion?, asked The Guardian at the end of its story about the end of the match.

Surrender, disappearance, exile

Fischer had not played a single competitive game since the World Championship match and presented Fidel with a list of his demands. When the sports association did not fulfill them unconditionally, Fischer withdrew from the match and Karpov became the new world champion without a fight.

For two decades, Fischer did not play a single competitive game – except in 1977, when the former world champion visited the MIT chess computer.

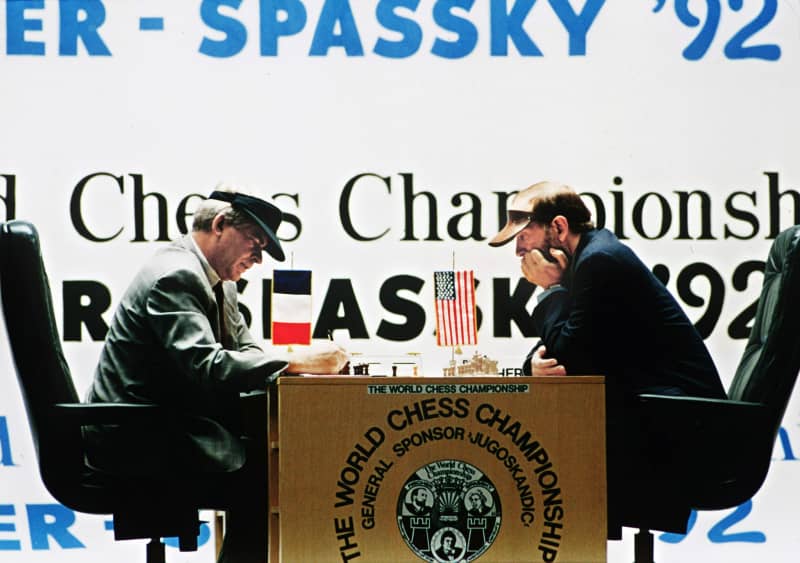

Long hidden from view, Fischer unexpectedly challenged Spassky to a rematch in 1992. Fischer believed he was still the true world champion and suspected that the championship matches played during his absence were rigged.

The rematch between Fischer and Spassky was played in Yugoslavia under the UN embargo. For violating the embargo, the US issued a warrant for Fischer’s arrest, which he evaded over the years in Budapest, the Philippines and Japan, where he was finally jailed for having an expired passport.

However, the former world champion never had to return to the United States and get to know its penal institutions. Fischer was granted political asylum in Iceland, which he and Spassky had put on the world map in the middle of the Cold War.

In his final years, Fischer raved about how the United States deserved the 2001 terrorist attacks and gave several anti-Semitic sermons in radio interviews. Many who met Fischer doubted his sanity.

If there were official diagnoses of mental health problems, at least they were never made public. Many have been guessed: among others, schizophrenia or suspicious personality disorder.

Bobby died in Iceland in 2008, leaving behind no statues or memorials. Robert James Fischer’s small white tombstone stands in the yard of a small white church in the village of Laugardælir outside Reykjavík.

Fischer was 64 years old when he died, as many years as squares on a chessboard.

_What thoughts did the story evoke? You can discuss the topic on 2.9. until 11 p.m._