The legend tells of a prosperous kingdom that was suddenly swallowed by the sea. There really were islands off the coast of Wales that disappeared into the sea in the Middle Ages, but the destruction was brought about by slow erosion, according to new research.

If you stand on the shore of Cardigan Bay in Wales on a quiet Sunday morning, you can hear the faint tinkling of church bells from the sea. So says one of Wales’ most famous legends. According to another version, the bells ring if some great danger threatens Wales.

You should be especially careful in the village of Aberdyf, because then it is the closest to the kingdom of Cantre’r Gwaelodia, which remained at the bottom of the sea. There were a dozen villages and towns with churches, and its fields were so fertile that one acre there was worth four elsewhere.

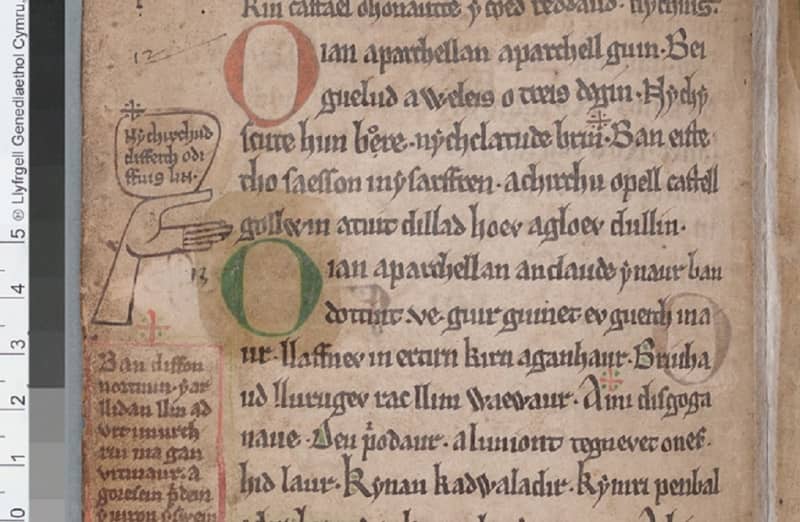

Thus confirms the legend, the first version of which was written in the first half of the 13th century as a poem in the Black Book of Carmathre. It has stored memories from centuries that were already history at that time. Among other things, there is one early version of the story of the Celtic king Arthur and his court wizard Merlin.

_You can listen to the song on YouTube Celtic

Meri surprised me in the middle of the party

Like Arthur and Merlin, Cantre’r Gwaelod and its destruction have also been considered just a good story, but according to research by the British universities of Swansea and Oxford, there is another side to the legend: islands have verifiably disappeared from the coast of Wales.

Of course, researchers disagree about the reasons for the disappearance, like the medieval storytellers about the destruction of Cantre’r Gwaelodia. They could even name the culprit. Some believe she was the king’s friend Seithenn, but the earliest version of the poem blames the Mererid maiden.

Cantre’r Gwaelod was such a low-lying coastal land that it had to be protected from rising water by ramparts. Guarding those gates was Mererid’s job.

One stormy night around the year 600, Seithenn was having a good time in the king’s palace, drinking plenty of wine and wooing Mererid. That’s why he didn’t notice how the sea swelled and flooded in through the open gates.

The prosperous kingdom disappeared forever in the waves and the fleeing people had to remember the past in new, meager places of residence.

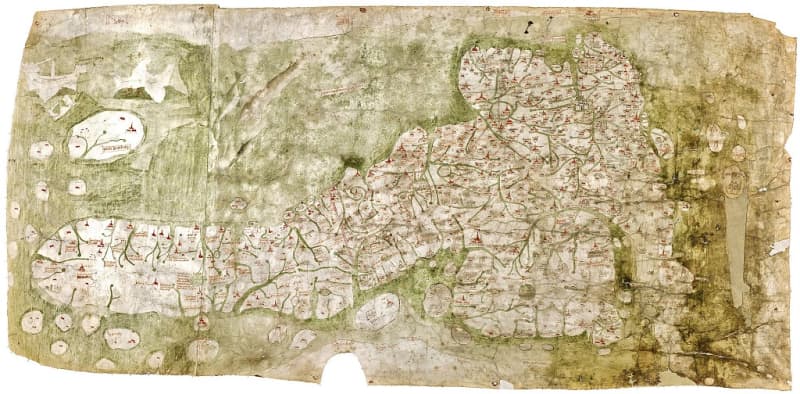

The research that proves the existence of the islands is based on the oldest accurate map that has survived of Britain, as well as geological and bathymetric surveys of the coast and seabed. Bathymetry measures the variations in the depth of seas, lakes and rivers.

According to its donor, the map named Gough’s map at the University of Oxford is estimated to date from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. The map shows two islands on the west coast of Wales that no longer existed in the 16th century. Each was about 180 square kilometers in size.

Although the markings on the map are partly difficult to interpret today, there is no reason to doubt its authenticity, as it is an unusually accurate output with the tools that were available at the time, the researchers say. The digitized map (http://www.goughmap.org/map/) can be viewed in detail online.

A Roman mapmaker who lived in the 10th century also made his own contribution to the research with his view of the coastline of Britain. Based on Claudius Ptolemy’s drawing, it was 13 kilometers further out to sea in Wales than it is today.

Over the millennia, erosion has eroded the land and created islands, which in turn have eroded into waves.

The fine-grained sediments that came with the ice are washed away in erosion, but the boulders remain in place. The location of the lost islands off the coast of Wales on the map coincides with the boulders lying on the seabed. They are still visible at low tide.

The Welsh call them sarnes, stepping stones. According to legend, they are the remains of a causeway along which the Cantre’r from Gwaelodi could pass to the current beach even during high tide.

The legend of the sudden destruction of Cantre’r Gwaelod may be based on the fact that a storm or tsunami hit the eroded coast, which was unable to withstand the natural upheaval.

– Understanding the dynamics of coasts has never been as important as it is right now. Some of the cities in the area we study are vulnerable to climate and sea level changes, and the first British climate refugees are predicted to set off from here.