Attila’s name has ended up in many stories as a synonym for a sadist, but according to a recent study, his most violent acts originated from reasons other than sheer greed or bloodlust.

IImasto change has been found to increase armed conflicts within states, and the statistical connection to the increase in migration is also clear. When uncontrolled, migration often increases social and economic tensions, which in turn can increase the threat of violence.

– Environmental changes caused by the climate can drive people to decisions that change the social and political system. Decisions are not necessarily straightforwardly rational, and their consequences can be negative in the long run, says Hakenbeck.

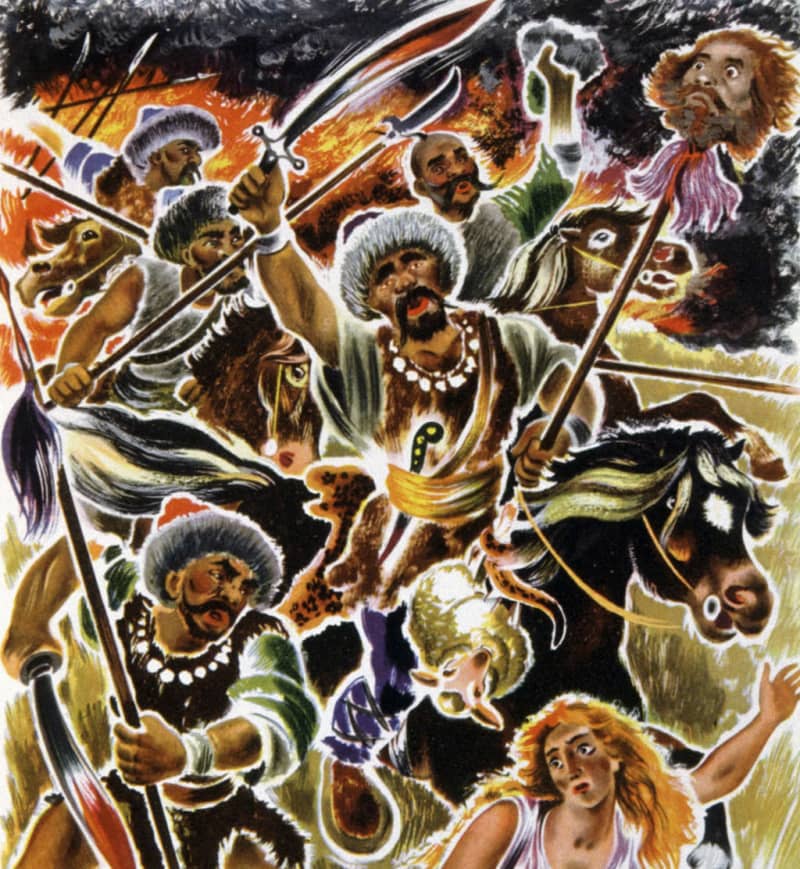

I guess many people think of Attila as the barbarian of barbarians, who always wanted more riches and gladly spilled the blood of Christians when the Huns spread to the west. At the time of Attila, the Roman Empire had already split in two. He delivered the final death blow to Western Rome.

The horses made the Huns move quickly, and the arrows shot from the horse’s back killed from a distance and effectively. After the avalanche, Attila’s troops no longer only destroyed the Roman outposts, but attacked the main forces.

The Roman historian and soldier Ammanius Marcellinus wrote already in the third century, before the time of Attila, that the Huns were \”ugly scarred faces whose cruelty knew no bounds\”. Attila became the Flagellum Dei, the \”Whip of God\” to the Romans, who plundered and destroyed their cities.

In historical research, however, the picture has long been known to be one-sided. The Roman elite wrote it from their own point of view, and not all contemporary descriptions of the Romans support the reputation of the Huns, or at least their leader, as bottomless greed for everything secular.

So what turned the son of a nomadic people who wandered into the Hungarian plain at the end of the 4th century into an unbeatable warlord who spread the power of the Huns to today’s northern Italy and all the way to France?

Fluctuation of the climate, according to a study published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology, based on archeological, historical and evidence obtained from annual tree rings. The big problems caused by the drought affected the aggressiveness of the Huns, the researchers conclude.

The annual rings of the oak trees in the flood plains of the Danube and Tisza rivers have recorded information about the growth years of the trees for two millennia. The Huns made their biggest attacks in the years when the Lusts were at their narrowest.

– Lustos provide excellent opportunities to combine climatic conditions and human activities year after year. Biochemical signs of drought coincided with the plundering expeditions of the Huns, says Büntgen.

Based on the isotope analyzes of the bone and tooth finds, the Huns both spread further and began to eat cultivated food in addition to nomadic food. On the other hand, some farmers in the border region seem to have joined to herd cattle and perhaps even fight alongside the Huns.

The economic balance between the established settlement and the newcomers was broken, and both had to resort to new strategies to secure their livelihoods and the structures of their society, Hakenbeck and Büntgen conclude.

According to their hypothesis, seemingly inexplicably violent violence was one strategy the Huns used to respond to climate extremes.

When Attila became the head of the Huns at the end of the 430s, their neighborly relations with the Romans were not unequivocally bad, although Attila was already filling his coffers more effectively than his predecessor by besieging Roman settlements and demanding ransoms.

– We know from historical sources that the diplomatic relations between the Romans and the Huns were complicated. At first, the security arrangements benefited both and the Hunnic elite received a huge amount of gold, but in the 440s, relations broke down. The Huns began to make repeated attacks on Roman lands and demand even more gold, says Hakenbeck.

According to the evidence presented by him and Büntgen, the fiercest Hun attacks were in the years 447, 451 and 452. It was in those years that the Carpathian Basin region, i.e. between the Carpathians and the Alps in Eastern Central Europe, suffered from extreme drought.

– The shaken economy due to the climate may have driven Attila and other high-ranking Huns to seek more and more gold from the Roman provinces, so that the mutual ties of the Hunnic elite and the operational capability of the military forces would have been preserved, says Hakenbeck.

He and Büntgen hypothesize that one of the reasons for the attacks on the provinces of Thrace and Illyricum in the past few years was more straightforward than gold: the Huns wanted food and cattle. However, more evidence is required to support the conclusion, the researchers admit.

Attila also demanded a coastal strip along the Danube, the size of which he defined as the width of five days’ journey. The reason for that could also be very concrete: perhaps he was looking for riverside pastures for the Huns’ cattle in case of another drought.

Attila died in 453 on one of his wedding nights. He had several wives. The last one may not have liked the marriage, as the bride is thought to have poisoned him. There is no certainty about that, just like not so many other things in Attila’s story.

According to Jordanes, Attila’s body was placed in three nested coffins: the iron coffin symbolized him as a conqueror, the gold and silver coffins his rank as a ruler.

Attila’s grave has been searched for in many places over the centuries. There is one possible clue in Jordanes’ text: before burial, the body was displayed in a tent made of silk cloth on the plain.

Did the Hungarian plateau mean? Attila’s headquarters was somewhere there, maybe his grave too. That is the main assumption of historians. However, there may not be anything to find anymore, because despite the precautions, the grave robbers may have had time to open it a long time ago.

Attila’s empire was short-lived. It disintegrated soon after his death in a power struggle between his sons.

*Listen to a radio program on Yle Areena about what the Huns set in motion in European history.*