A white paradise in the Käsivar desert turns to hell in an instant

More than 100 000 hikers visit the Käsivar wilderness area every year. The growth of tourism in wilderness areas raises concerns about both safety and the carrying capacity of nature.

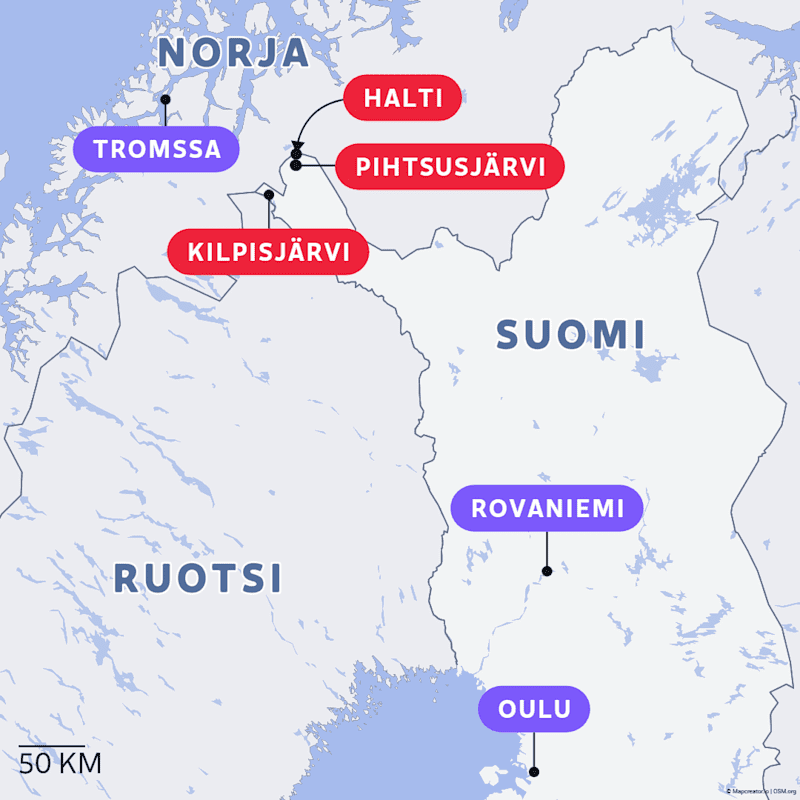

A snowmobile of the Lapland Rescue Department turns in front of the Pihtsusjärvi desert cabin in the Käsivarri wilderness in Kilpisjärvi.

Soon another will follow. The paramedics rush into the room.

One of them will be out in a moment.

– Does it work somewhere here? He asks the skiers who stand in front of the cabin.

The answer is no.

At least not anywhere nearby, and especially a cellphone. The nurse’s look is serious.

We are in the middle of the wilderness, 40 kilometers from the village of Kilpisjärvi, following how Arctic conditions affect the safety of growing travelers.

In Pihtsusjärvi, the problem becomes instantly concretized: help is far away, and you are not on the ground, let alone cell phones.

Snowy North attracts tourists

For example, the other year, according to Metsähallitus Nature Services, a total of more than 114,000 hikers visited the nearby areas of Kilpisjärvi village and in the wilderness area of \u200b\u200bthe Käsvarre.

However, the increase in the number of tourists and the arctic conditions are a combination of elasticity.

According to Metsähallitus, the sensitive nature of the area is being tested, especially if, for example, sledding and other motorized business in the area are growing further.

The biggest concern for local entrepreneurs is the safety of growing travelers: if something happens, help can be surprisingly far away.

The nearest hospital is in Norway

In Pihtsusjärvi, the nurse can connect to the emergency center with a satellite phone some distance from the living room.

A helicopter would be needed. The closest one is on the Norwegian side in Tromsssa. It would take the patient directly to 160 kilometers to Tromsa University Hospital.

However, helicopter is not coming.

The snow dumps and the visibility is minimal. Then even a rescue helicopter does not know where to land.

Anyone can get a safari permit

In the wilderness area, only self-employed travelers may not fall into trouble.

According to Metsähallitus, over the last five years alone, about twenty new safari entrepreneurs have entered the small Käsivarre area.

The problem is that any company can, by application, get a so -called safari license from Metsähallitus to the Arctic wilderness. This is guaranteed by EU equality legislation, according to which every company must be treated in the same way.

For example, no local knowledge is required.

The supervising authority is concerned

The safety of sled safaris in Finland is monitored by the Finnish Safety and Chemicals Agency Tukes.

According to Leinonen, Käsivarre Wilderness and the Utsjoki Kaldoaivi are one of the most challenging areas in Finland. Special attention should be paid to the safety plans and regional expertise of safari companies there, says Leinonen.

The new Consumer Safety Act, which may enter into force this spring, could also allow it.

According to Leinonen, companies operating in the regions could require increased expertise, for example in avalanches and ice skills and rescue operations.

\”You should also be able to demonstrate that know -how,\” he says.

Current safari licenses are valid until the end of this spring.

Metsähallitus is currently exploring whether more permits should be reduced in the future.

– We also have to think about how responsible activities it is to grant permission for everyone, says Martikainen Metsähallitus.

According to Risto Anunt, the idea sounds good.

– Here when bad weather comes, it comes suddenly. Then it doesn’t help if you have previous experience only in southern Finland, he says.

The journey continues

In Pihtsusjärvi, the sled of the rescue department turns on a narrow snowmobile trail towards the village of Kilpisjärvi.

In the opposite direction, towards the elves of just over ten kilometers, there are two sled safaris and several ski groups.

The breeze and snowfall do not seem to break anyone’s going.